It’s all easy enough until the last uphill jag.

On the right there. For the show-offs.

Þjófafoss on the Þjorsá is a lovely spot, rich in wildflowers, lichen and wondrous lava blobs under Búrfell and Katla, and then there are the falls, which are stunning.

Historically, this was a green land until 1104, when the volcano Hekla filled it in. After that, it ran as a high rapid in a monumental flow. Now it is a fall. The water of the Þjorsá is diverted away from it to run two power plants. It stands as a warning against becoming too enamoured with “Nature” in Iceland. It is often an industrial product, either as a constructed landscape, the planted forests of the North East …

… or even the great fjord lake, the Lagarfljót, in the East…

Not to mention the Blue Lagoon, which is the outflow from a power plant, too.

There are many more examples. The great black sand beaches of Heraðsandur, for example, with its re-engineered rivers and outflow strewn across the entire East Coast by wind, currents and tides.

This industrialization of landscape raises many questions. If this were happening in Canada, it would be called encroachment on Indigenous space, which it would be. Because there is a myth that there were no people living in Iceland before the Icelanders came in the 9th century, Icelanders can escape that one. There were Irish, and walruses, but someone the Irish don’t count and the walruses are, well, not human, although I don’t see why that should make a difference. We are looking at walrus country without walruses.

Instead of carrying the weight of settler colonialism, which burdens countries like Canada, the United States, Australia and South Africa, Icelanders claim a history of settlement, of claiming and developing wild land in the middle of the Atlantic. It sounds benign, but what it means is the very industrialization of landscape I have described above. Even sheep, all 3,500,000 of them in the country, are industrial, and have turned the country from a birch forest into a desert.

The wind takes over as soon as their hooves cut the sod.

Iceland markets itself as pristine nature now:

And that’s the other side of this story. Wonderful places like the Lagarfljót, Heraðsandur and the Jökulsárlón are embedded in a story of global climate change, melting glaciers and eroding dunes. So much of what there is to see in Iceland is of this process. It doesn’t make it less beautiful, but it does make it fraught. It’s not pristine nature that one views in Iceland, so much as nature’s reaction to human industrialization, often by visitors who are a vital part of that industrialization. Nature is, pure and simple, an industrial product in Iceland. It is still wonderfully beautiful, but it is more an image of technology for a technological people than it is a land in and of itself. Even this blog, after all, is a technological product.

A trip around Iceland’s Ring Road is a great opportunity to watch other people taking a trip around the Ring Road.

No Need to Say Where. That’s Not the Point.

In turn, they get to watch you taking a trip around the Ring Road. It’s a thing. For this, one needs Iceland. You couldn’t pull it off in a city square at home. No way.

It just wouldn’t be the same!

In bilberry season!

I once asked a waitress in Reykjavik why Icelandic lamb was so superior. “It’s the berries,” she said.

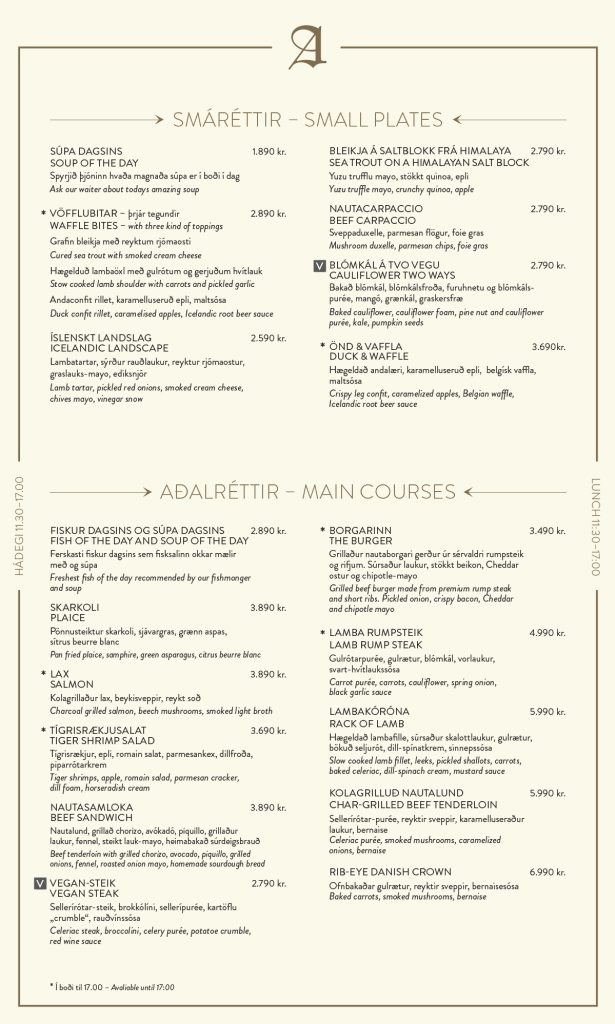

Well, a lamb dinner in a nice restaurant in Reykjavik, like the Apotek …

… is going to cost CAD$65 for the main course alone, so, you know, $260 all-in for two. For this reason, there are bilberries, which are free for all who wish to marinate themselves in the rain and the wind. Highly recommended.

In winter, there are no bilberries. And no lambs. You’re on your own.

Once there were fuel stations for travellers. They were built on farms and were the modern equivalent of a service economy that had sustained wealthy farms for many hundreds of years. Some even had garage and tire services and predated the Ring Road of Dutch Camper Company fame. Many of the country hotels in Iceland still follow this old model of serving travellers on farms. The fuel stations are gone now as working centres, though. The more remote of them have been replaced with a lone pump, an automatic card reader, a light, and the bright sign of a national chain in a corner of a field. Not at Starmyri, though!

This translation of a bustling service centre on a rich farm is a bitter story. Once on the gravel road north along the East Coast from Höfn, with valuable shore rights at the mouth of the Seal River…

… and a good, sheltered landing, it was isolated by the sea by black sand drifting south by rivers re-engineered in the North during the diversion to create the hydroelectric power for the aluminum smelter in Reyðarfjörður.

The result was a new East Coast built from lagoons and long, black sand beaches…

…beloved of tourists and useless for farms that live in 1100 years of time, not the continually re-occurring present and fictional pasts and futures of 21st century time.

Still, as you can see…

… the whale bones of an older past keep it company now, as if they were the busts of roman senators on their plinths. This is beautiful art-making. You can see 1100 years of life at once.

Whatever Siberian forest this tree grew in before washing west and south and landing on the Starymyri shore, I bet it never expected to achieve eternity like this! And, yes, at Starmyri, where the sheep pastures have eroded away in the wind…

… the shore is blocked by industrial sand, shore rights are extinguished and the road has been moved away from the farmyard, the farm still manages to draw sustenance from travellers.

Each cabin offers an ideal Iceland, framed as a work of art.

Like many important things in Iceland, you have to find the history yourself, on the principle that you only need to know what you need to know and if you find something else, then you know and don’t need to be told, in this country that dresses up as pristine nature, her newest artistic dress.

An old farmer built this artwork in his retirement. The family keeps it in his memory. What a clever man!

Iceland’s great mountain is not on the Ring Road, which is an arrangement of highways across the width and breadth of the main chunks of Iceland that allow tourists to flow through the country on “road trips” and, with luck, meet only professional tourism operators. This allows the country to get along with things and to pay for its roads. When you’re off the Ring Road, though, you have to be clever. The people of Snæfellsnes have hit on a couple of solid ideas. They won’t tell people that the name of the town that hosts their tourism marketing staff, Hellissandur, means The Sandbar from Hell, and they promote the daylights out of the idea of day trips from Reykjavik to view the sites. No overnight stays necessary. Clever.

Welcome to the Centre of the Earth

It makes a lot of sense. If people come for longer, they won’t leave, and if they don’t leave, they won’t need a tour bus, and if they don’t need a tour bus, what then? These are the big questions. The mountain and its snow spirits (I mean, look at them up there!) do not need to answer. It is an inspiring purity of presence.