The greatest beach, with the greatest river, on the greatest fjord. This is why Gunnar came home from Europe on the brink of war.

Looking north from the Stapavík-Njarðvík Trail.

Where better to survive the end of the world?

On his reading tour through wartime Germany, Austria, Poland and Czechoslovakia in the spring of 1940, Gunnar Gunnarsson said that the darkness of Iceland was as much the soul of Icelanders as the long days of summer light. It was a statement meant for a Nazi audience and expressed what he saw as the one common point between Nazi culture (his main audience) and his own: a belief that people sprang from the land and represented its highest aspirations. In Iceland’s case, that also means (says Gunnar) from the darkness and the light, presumably in how they are caught by the land. It was a peculiarly pre-modern idea expressed at the height of the modernist period. Now that we all live in a post-modern era, in which everything is an image or a belief, Gunnar’s expression appears a little strange, if not repugnant, or it would, if the light and the darkness were not still there, however he expressed them in that troubled time. This is a troubled time, too, so it might be interesting to look at what he saw as an answer to these troubles: darkness and light, that are the same when viewed through a human eye.

Rather than being a Nazi view, that is, at heart, a profoundly Christian one, in a specifically Icelandic sense, for in Iceland Christianity made only a light break between Norse and Christian belief, uniting them through a common ethical ground. Ground like the image of Kolgrafarfjörður at first light on Christmas Eve Day above. Gunnar was buried in a Catholic cemetery on Viðey, to be with his wife, but the impulse within this ethical ground remains profoundly Lutheran. It represents a choice. It gives human nature as the ground in which this choice is made, ground that is formed by experience with scenes like the one above and so scarcely separable from them. Gunnar told the Germans that no-one but a child born to Iceland could act rightly in its landscape. It is the kind of statement most often made about language — that a native speaker of a language never makes a mistake in it, while a non-native speaker must always follow set rules, lest a mistake be made and nonsense result. This then, is Gunnar’s language:

If you see mountains only, look again. Better yet, go there in the winter, when you are a body among other bodies (non-human ones) there, in a syntax in which you are but one word, one through which human language comes.

The approach of winter on northern earth is described by the angle of the earth to the sun, but look …

… is it not a story of light rather than mechanics? Here in Grundarfjörður, is it not a story of the light …

… is it not a story of light rather than mechanics? Here in Grundarfjörður, is it not a story of the light …

…separating from the dark earth and so revealing it?

…separating from the dark earth and so revealing it?

It is not a scientific description, and yet as the light falls the earth becomes more purely light, and more purely cold.

It is not a scientific description, and yet as the light falls the earth becomes more purely light, and more purely cold.

Light is cold, in other words. This is wisdom, too. If we’re going to beat global warming, that light is going to need the respect now given to mechanics and technology. So is the cold, because they are the same. It’s not a linear understanding; it’s a global one. It is earth-thought.

Light is cold, in other words. This is wisdom, too. If we’re going to beat global warming, that light is going to need the respect now given to mechanics and technology. So is the cold, because they are the same. It’s not a linear understanding; it’s a global one. It is earth-thought.

Technology is not the end to science. It’s great stuff, but it’s not the goal, whatever the goal might be, or if it is the goal, then the goal is not of this earth, and that is a judgement humans have no right to make.

Technology is not the end to science. It’s great stuff, but it’s not the goal, whatever the goal might be, or if it is the goal, then the goal is not of this earth, and that is a judgement humans have no right to make.

These are hard ironies. If technology is the path away from the cold, it is the path away from the sun.

It is the path away from the earth.

The knowledge and traditions of how to live with the earth are not lost. Here are two operating manuals. There are more.

The poets still know something of the earth.

It can be read by the sun. They know how to do this: how to read the sun, the earth and themselves on the body’s face.

They embody the sun. Fences aren’t for the light, and yet they cut it, nonetheless, …

… until the world becomes a series of fences. These are hard ironies, but not causes for despair; they still catch the light.

We can still follow it, but one thing remains primary. We have a right to the sun, to the earth, and to the cold.

The cleverness of ancient methods of mediation between earth and light are a richness of capacity rooted in ancient verse forms.

Make no mistake. This stuff can be read in detailed literary ways, and that’s an important tool for entering this technology. Read more by clicking here. Still, until you can read it in the earth, you have not entered its light.

Discarding this light, simultaneously of sun and earth and cold and warmth and mind, for physical technology is exactly what it sounds like: discarding them, and all their alternative forms of warmth…

… for physical technology, which is important.

… for physical technology, which is important.

But the path remains the old one.

It is to make people out of the earth. It is to bring the wanderers home.

It is to make people out of the earth. It is to bring the wanderers home.

Here’s one manual:

Here’s the obligatory legal warning to users.

Here’s another one of the manuals.

Here’s Gunnar’s quote from the title page, expanded in its original context:

He that entereth not by the door into the sheepfold, but climbeth up some other way, the same is a thief and a robber. 2 But he that entereth in by the door is the shepherd of the sheep. 3 To him the porter openeth; and the sheep hear his voice: and he calleth his own sheep by name, and leadeth them out. 4 And when he putteth forth his own sheep, he goeth before them, and the sheep follow him: for they know his voice. 5 And a stranger will they not follow, but will flee from him: for they know not the voice of strangers. John 10:1-5

Here’s its expansion:

11 I am the good shepherd: the good shepherd giveth his life for the sheep. 12 But he that is an hireling, and not the shepherd, whose own the sheep are not, seeth the wolf coming, and leaveth the sheep, and fleeth: and the wolf catcheth them, and scattereth the sheep. 13 The hireling fleeth, because he is an hireling, and careth not for the sheep. 14

In other words, look after your sheep; look after your land; be a man about this:

Gunnar left his hireling life in Europe

… and went to farm sheep in Iceland, from this house at Skriðuklaustur …

… after writing that. Was it a mistake? Well, he didn’t last long there, but the commitment was real.

… after writing that. Was it a mistake? Well, he didn’t last long there, but the commitment was real.

And so light comes. Gunnar meant that poetry and the land and honour were one. It was not literature. It was not a metaphor. This is not a metaphor.

Gunnar meant that poetry and the land and honour were one. It was not literature. It was not a metaphor. This is not a metaphor.

Think again. This is a nature preserve in the Whale Fjord in West iceland. It is also one of the runways of the fighter base that protected the Allied Fleet during the Battle of the Atlantic during the early 1940s. Here’s another view. Back then, this fjord would have been filled with ships, protected by fighter cover and a submarine net across the mouth of the fjord.

It is also one of the runways of the fighter base that protected the Allied Fleet during the Battle of the Atlantic during the early 1940s. Here’s another view. Back then, this fjord would have been filled with ships, protected by fighter cover and a submarine net across the mouth of the fjord. This is the naval base today.

This is the naval base today.

Iceland has, wisely, left this history almost unacknowledged, and has given this land to the birds. We can honour that forever. We don’t have to stop honouring that wisdom any time soon.

In his speech “Our Land”, with which he tried to prevent a German invasion of Iceland in 1940, Gunnar Gunnarsson wrote that the long months of Icelandic winter darkness were as much a part of the Icelandic soul, in a positive way, as the long months of light, and that an Icelander, a person of the land, could not be removed from it. I read that as an attempt at planting the suggestion in Hitler’s head that an Icelander was a true person of the land, and a German was not — either in Germany or Iceland. Those were dangerous and courageous words, whether they were true or not. There is a report that after Gunnar gave this speech in forty cities in Germany and Occupied Europe, Hitler screamed at him and threatened him with … wedon’t know with what, but most writers threatened by Hitler and his inner circle were threatened with death should they ever write again. Gunnar scarcely did. Was it that he was frightened? Or was it that his work was over, because the British invaded within two weeks, denying any possible German foothold? The answers are lost to history, but the observations about the land remain. I have come in these months of darkness to try to understand. Look how dark it is here:

What do you think? Is this darkness?

In his book Advent, another of Gunnar’s psychological manipulations, Gunnar wrote about a man’s true friends, a dog, a ram and a horse, and how they gave their lives freely to a man who one day would have to take those lives.

Gates optional.

In Advent, Gunnar was writing about many things: Christ, writing, Gunnar, and the Germany of 1936. Was he telling his German readers that Hitler would ask for their death one day, in ways without the Christian mercy or poetic symbolism of his own faith? We will never know (although it seems likely), but the animals remain, as human companions in this vast space.

Is that darkness? Is that an empty space? Is it people who spring from this land, or something else? Faith perhaps? At any rate, people are not alone here.

Is that darkness? Is that an empty space? Is it people who spring from this land, or something else? Faith perhaps? At any rate, people are not alone here.

And, let’s face it, with his lines about darkness, Gunnar was not talking about Iceland. He was talking about something symbolic, something psychological, something that did not come from a world of light but which was expressed, in Gunnar’s Iceland, in a world of light. It is not something which falls easily into non-Icelandic categoreis. The image below shows a place of human habitation in Gunnar’s world.

And, let’s face it, with his lines about darkness, Gunnar was not talking about Iceland. He was talking about something symbolic, something psychological, something that did not come from a world of light but which was expressed, in Gunnar’s Iceland, in a world of light. It is not something which falls easily into non-Icelandic categoreis. The image below shows a place of human habitation in Gunnar’s world.

Notice how the house is not a dwelling. The land is the dwelling. The house is a small shelter to protect human weakness, but the dwelling place is out in the fields, between stone and sky. Even the water flows with primal force here: the sky made liquid.

Notice how the house is not a dwelling. The land is the dwelling. The house is a small shelter to protect human weakness, but the dwelling place is out in the fields, between stone and sky. Even the water flows with primal force here: the sky made liquid.

Even the setting sun. This is Borgarfjördur, where Gunnar bought property from his book sales, before moving back to East Iceland from Denmark in 1939, shortly before his disastrous (or successful?) speaking tour in wartime Germany. This would be the land and darkness he was talking about, here in one of the seats of Christian Iceland, on the shoulders of its darkest pre-Christian sagas. Let this be a warning to all of us trained in post-Christian intellectual traditions: we do courageous men such as Gunnar wrong to read him outside of his faith.

Today, I’d like to welcome Friederich Dürrenmatt (1921-1990), Swiss playwright and crime novelist, especially the former. He and Gunnar should have been friends. They were both energetic writers, both pioneers of criminal novels, and actively wrestled over a long period with ideas of ethics, morality, judgement and faith.

Today Dürrenmatt’s old villa above Lac Neuchatel has been turned (on his bequest and with his financing) into a museum of … not his great twentieth century plays or his semi-autobiographical detective novels but his paintings, drawings, etchings and, well, look …

Today Dürrenmatt’s old villa above Lac Neuchatel has been turned (on his bequest and with his financing) into a museum of … not his great twentieth century plays or his semi-autobiographical detective novels but his paintings, drawings, etchings and, well, look …

Could be cheerier, right? Well, his youth was spent in Switzerland during the Second World War, and just over the border things looked much like that, actually. Worse yet, when he was quite young, he was a member of the Frontier Club, a parallel movement to Nazism within Switzerland. He soon gave it up, but he carried the guilt forward for his whole life, and, as he put it, without a confessor but himself he had no way to expunge it. One of his most profound attempts was through the play The Minotaur. We know the story from Ancient Greece: a creature half-man and half-beast…

is imprisoned in a maze …

… the hero comes to slaughter him …

… which makes him into a beast …

… and the beast into … well, Switzerland portrayed as a Roman Amphitheatre in which lions are eating Christians and the whole works. Either that or sunning on the riviera at Montreaux.

I made these images in 2010. When I was there in 2008, this amphitheatre was an image of the bankers of Zurich, being caught at a transaction they wanted to keep secret. The maze and amphitheatre was the frame of the image. In two short years, the curators came up with the improved version above. Here it is below (notice the maze of images that surround it. The whole building is the Minotaur’s lair.)

The thing about Dürrenmatt’s play is that he fills the stage with mirrors so that even the audience cannot tell which image before them is the minotaur and which is a reflection of it; one might want to slaughter it, but where does one strike? Perhaps the image slaughters the self. Dürrenmatt was concerned with issues like this. He took protestantism more seriously than protestantism.

His radio play “The Accident” is perhaps most indicative of his method. In it, a travelling salesman suffers a car breakdown in a remote mountain village, on his first day on the job. He is directed to a villa, where a retired judge from Zürich (a foil for Dürrenmatt) and his friends are having dinner. The judge agrees to put the salesman up for the night, in return for his participation in a gentlemanly game. The salesman naively agrees. The game is an interrogation, in which the judges (retired) get to ply their trade by interviewing their guest (the salesman), on the principle that everyone is guilty of something; one only needs to find out what it is, and then absolve the person through sentencing. Well, I won’t give away the plot, but suffice it to say that the salesman’s secret is found, judgement is passed and then trifled with, and ultimately the audience leaves the stage under judgement itself, to argue the nuances away within society, in the bars and night cafés of Zurich. Every one of Dürrenmatt’s plays is a trial. It is the audience that is put on trial. There is no absolution. It is all quite shocking and, for a non Christian, exquisitely Christian, but you see, Neuchatel, where Dürrenmatt lived, actually is home to the minotaur. Sure, the guy is Dürrenmatt, but he is also this (well, androgynous) guy:

We are looking to what is perhaps an 8,000 year old Stele, carved several thousand years later by the Celts (who are the Swiss). This story of a beast becoming a man, which is the human story, takes place in Neuchatel without a break. For Dürrenmatt, a quintessential Swiss, civilization is a process of taming, which sometimes is a process of caging, and when you do it to yourself… what then? Why, you deflect it upon your audience, and send them home to wrestle with the mystery that cannot be resolved. That, I offer, is Gunnar’s story. All that’s different is that he has come to the story before the Second World War, and Dürrenmatt came to it during it, and Gunnar came to it from Nordic prehistory, while Dürrenmatt came to it from Swiss prehistory. For both of them, protestantism was larger than the church. It was kind of defiance in and of itself — and not necessarily of a negative kind.

Next: Gunnar’s Bind

Gunnar Gunnarsson was Icelandic and a Christian. He was, in other words, an Icelandic Christian — a faith that saw few points of breakage between Nordic ethical norms and Christian ones. What it mostly found instead was a purification of them. That’s no real surprise. It is a faith which settled the Island at the same time as Norse belief, and came to accept a shared relationship with it, ratified at the Thing of 999/1000 and cemented by Thorgeir casting his house gods into the Goðafoss and letting the water carry them away into the spirit of the land.

Goðafoss

With such a conjoined history behind him, Gunnar the Icelandic Christian felt that his calling as a Skjald, a shield poet in the old Nordic style, enabled him to speak truth, which his faith demanded, to power (Hitler, on March 28, 1940), and protected him from retribution — not as a Norse skald but as an Icelandic Christian one (the English word that comes from the skald tradition is scold). Cultural couplings abound. In Icelandic Christianity, for example, we see Eve giving birth to two groups of children: the hidden ones and the revealed ones. The hidden ones are the elves — usually a nordic element; certainly not a standard Christian one. The revealed ones are human — a more familiar Christian motif. Sure, this is a folk story and not part of canonical faith, but it’s one that comes from a country in which the Lutheran faith did not arise out of princely protest against the circumscription of regional and local power by a distant papal authority, couched in terms of a popular uprising against cynicism, as it did in the Holy Roman Empire German Nation (now Germany). Those were Luther’s stresses, and if he retreated into his faith, singing “Ein Fester Burg ist Unser Gott” (“A Mighty Fortress is Our God”) he can be forgiven for trying to find something solid in a world that treated faith as a weapon in the hands of power rather than a weapon against such abuses of power.

The Poet Goethe Sketched The Wartburg in 1777

Because of this sketch, it became the romantic symbol of the call to a German State. Goethe and Luther could have had a lengthy discussion across the divide of their different centuries about being conscripted into being symbols of power.

There’s an old story in Wartburg Castle above Eisenach, Germany, of Luther sitting in his small room behind the guard room, translating the Bible into German, when he was interrupted by the devil and threw his ink bottle at him in frustration. The ink stain is still on the wall, the tour guides will happily show you, although they can be forgiven for leaving out the detail that it has been artfully repainted many times over the years. The thing is: Luther was not in the castle of his own free will. After being excommunicated from the Catholic Faith in Worms, on the Rhine, he made his way back along the ancient road, the via regia, to his home in the East as an outlaw. Luther was born just off the road in the forests and coal mines of Hessen and knew about the road and the forest. By day, the road belonged to the king. By night, it belonged to bandits likely as not to kill you for a button. He fully expected death, and then was kidnapped, brought up to the Wartburg, told he was being a fool, and entreated to translate the Bible instead of giving up his life.

The Wartburg in 2010

That little room behind the guard’s room? Come on. The castle had a lot of rooms. This one was a jail, where his warders could keep close watch on him and bring him bread and water from time to time until he agreed to hand over a fully translated work. The devil? The prince, of course, who demanded this text to strengthen the hand of German princes fighting for independence from Rome. The way to escape from imprisonment in the great Wartburg castle? Through faith. Hence the hymn about the Mighty (Mightier) Fortress. It was the way in which St. Elizabeth of Hungary escaped the Wartburg centuries before, as well: she gave the poor the bread and water given to her by her confessor for defying the king, and thereby starved herself to death. There were miracles along the way (forbidden bread for the poor transformed into roses by faith), which tell a story of a true heart overcoming all — a standard folk motif, and a standard Christian one.

In the next several days I am going to speak about Gunnar’s Christianity, within his books and within his contemporary context, but today I’d like to point out a parallel: Gunnar and Luther are spiritual brothers. Neither were true protestants: Luther never did want to dispose of allegiance to the Pope; Gunnar was buried in a Catholic graveyard in Iceland.

Gunnar’s Resting Place, Viðey

Both Gunnar and Luther spoke truth to power, Luther to papal power and Gunnar to Hitler. Both were feverish writers and polemicists. Both attempted to influence power and were used by it for its own ends: Luther became the spokesperson for a break with papal power; Gunnar, who wanted to assert Nordic independence, was given fame, wealth and readership by being published by the German propaganda ministry, to further the annexation of Scandinavia to Germany. Both were imprisoned for their principals, left in the end with nothing but their faith: Luther in the Wartburg and a new faith imposed on him by political circumstances and machinations, that did not always fit him well; Gunnar in Skriðuklaustur, banished there and told not to say another word, on pain of physical and spiritual annihilation. That’s a guess about Gunnar, but not a wild one. It is precisely what the German writer Ernst Wiechert was told after he spoke publicly against Hitler — twice. After six weeks in the Buchenwald concentration camp, which nearly killed him, Wiechert was sent home under house arrest, which lasted from 1937 to 1945; after returning home in 1940, Gunnar hardly wrote at all. He had become an Icelandic protestant, protesting the very notion of restrictions to his power as a skjald. His form of protest? Silence. An exact representation of his place in the world of power and of Iceland itself, and an exact embodiment of the power of his rather individual faith.

Tomorrow: Gunnar and Dürrenmatt. Soon: Gunnar and silence.

When I left Skriðuklaustur a little less than a year ago, a fox ran beside me as I turned away from the lake towards Egilsstaðir and a glorious, sunny flight (with Air Iceland chocolate) to Reykjavik. I took it as a good omen. On my hard drive, I had the notes towards a book written during four weeks of becoming so immersed in Gunnar Gunnarsson’s work that it was written in the death-dance style of his novel Vikivaki. It is now finished and ready to find its way into the world. It begins like this:

A DICTIONARY OF ATLANTIS, by Harold Johanesson

An introduction to Gunnar Gunnarsson’s books of literary spy craft Islands in a Giant Sea, The Shore of Life, The Black Cliffs, Vikivaki, The Gray Man, and The Good Shepherd by Gunnar Gunnarsson, in the form of Vikivaki and in the light cast upon them by the essay, Our Land, which Gunnarsson presented to Hitler and Goebbels in the wartime spring of 1940.

Atlantis? Yes, Gunnar took a cruise there with his mistress and a group of Danish and German intellectuals and literary figures dabbling in racial theory, in June of 1928. The trip changed his life and set him on a twelve-year-long program as a secret spy working entirely on his own, without confiding in anyone, to change the course of the foreign and military policy of the Third Reich. Here’s the image that haunts me, of the day in the spring of 1940, just after he hoped to stand triumphantly before Hitler. Quite the opposite was the case.

Secret Agent Gunnar (in the black coat).

Note the fencing thrust of the right leg of the SS Officer next to him. That’s Otto Baum, who would soon capture Norway for Hitler.

My book shows both what Gunnar had in mind and how his use of literature to further his cause created a genre both ancient and 75 years ahead of his time. My next tasks are to find a publisher for this book, to write a play about Gunnar’s meeting with Hitler, and to open the book up into a series of literary essays about Gunnar’s works, their form and their context. 20th Century literature has lost one of its central stories. By sheer good fortune I have found it. There is much exciting work to be done.

So, what happens to best-selling author Gunnar Gunnarsson’s public after his archetypal stories of Icelanders living in a raw, Nordic landscape …

… fall out of fashion in the new, post-war Germany that is partly an American colony and partly a Soviet one …

The Social Unity Party of Germany Grows into a New Kind of Party

Well, that’s what they thought back in the 1950s.

… looking to the future because the past is probably a pile of bricks out in the street?

Downtown Berlin in the Early 1950s: a Cold War Battleground

With Baltic Gemany lost, there’s not really much interest in looking to the North anymore.

This is the era of re-imagining Germany on a European cultural, rather than a nordic cultural foundation (Well, in the West, at any rate,) and especially not on the military or racial foundation of the 1930s and 1940s.

500 Years of the Gutenberg Bible

Stamp from the New Post-War State of the German Communities (West Germany)

This is the era of sausage stands springing up in the ruins.

Bratwürst Stand, 1952

Women start to take charge of things, after the men messed up big time.

This is the era of the canoe on top of the Volkswagen and the first communist cardboard car.

The Height of Modernity

What you get for reading too many Westerns. Especially after trying to drive to Smolensk in much the same get-up (The Volkswagens of the early 1940s were kitted out as amphibious assault vehicles … i.e. jeeps!)

This is the 1950s. Here’s what Gunnar’s readers are snapping up at kiosks little different from that sausage stand above.

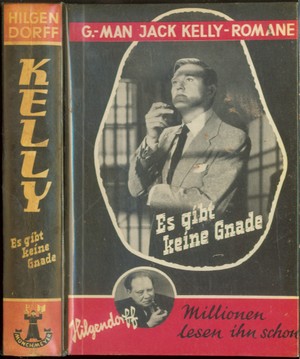

FBI Agent Jack Kelly: There is No Mercy

FBI Agent Jack Kelly: There is No Mercy

Hilgendorff: Millions Have Already Read Him

Herman Hilgendorff (Actually, H.C. Müller or Kurt Müller) wrote nearly 1000 books (!!!): most of them Westerns, FBI crime novels and British spy novels. (Long before the World War II Agent Ian Fleming spoofed the genre with his James Bond pulp novels.) Müller was one of the few crime novelists not banned by the Third Reich. And what is in these books that drew the Germans to them, and away from Gunnar’s more thoughtful, physical and eternal visions? This alternate book title (a cheap 60 cent edition) ought to show you …

Jack Kelly, FBI Agent, at the Controls of the Robot that is Trying to Shoot Him

Jack Kelly, FBI Agent, at the Controls of the Robot that is Trying to Shoot Him

Does the robot look like a man? 100% Only Jack Kelly can tell the difference.

And who has constructed these robots? Why, a so-called Mr. Carefree, who promises to remove pain and suffering from people’s lives, for cash, in a process which usually involves underhanded death and destruction to someone else, a man who remains hidden and unknown, because he fronts even himself as a robot. And who is he? A hateful man. A theatrical agent from the 1930s. Yeah, this guy, you got it:

Joseph Goebbels, Third Reich Propaganda Minister

Any film made in the Third Reich was cleared by him.

Any book published in the Third Reich was published by Goebbels. Here’s one of those books:

Advent in the Highlands, by Gunnar Gunnarsson

This is the edition approved by Joseph Goebbels.

Here is “Mr. Carefree” with with one of his robots.

Ah, But Which is the Robot and Which is the Real Mr. Carefree?

And then there’s the artist who sculpted the robots. Is he the German everyman? Is he a resurrected Jew, freed from the camps? Is he this man?

No, that’s just Gunnar, living on in a Europe that had left its own images for ones from Asia and America. Meanwhile, HIlgendorff continued to rewrite the Nazi period in his pulp novels, under the concealment of the popular images of a new, non-European age. It’s fascinating to watch modern Europe birthing itself in the darned things. Oh, and who is Jack Kelly, really? Aha, look again:

No, that’s just Gunnar, living on in a Europe that had left its own images for ones from Asia and America. Meanwhile, HIlgendorff continued to rewrite the Nazi period in his pulp novels, under the concealment of the popular images of a new, non-European age. It’s fascinating to watch modern Europe birthing itself in the darned things. Oh, and who is Jack Kelly, really? Aha, look again:

I bet he loved sausages.

I started this blog a year ago, talking about tuns. Here’s the result of a year exploring them or just wandering through them (under the observant eyes of ravens.)

You Are Never Alone in Iceland, Hengifossá

(Well, unless you’re always looking for humans for company. In that case, it might be best to stay in Reykjavik.)

Today, I’d like to illustrate an observation that it’s not people who are creative, but space. Ah, you might ask, what is a tun that it might lead to an observation like that?

Icelandic Horse Scratching Its Head

A tun is something that you can observe (and take part in) everywhere in Iceland (and in the North). Here’s a tun in Denmark (the former colonizing power, grrr):

Half-Timbered Danish Farmhouse

Half-Timbered Danish Farmhouse

Den Fynske Landsby, Fyn, Danmark. The working courtyard in front follows the ancient Norse (and thereafter Icelandic) architectural model of a tun, an open air working room between buildings.

A tun is a building without walls or roof, where the money-making activity of the farm took place, and where the manure (the dung, a variant of the word “tun”) was stored, which could be spread on the fields to create future wealth. It is the source of economy.

Horse-drawn Wealth Spreader Waiting for Re-use

Hedge fund version 1.0.

The tun usually connected to the track to the next farm, or out to the world of trade. Here’s a variant on a tun, from East Iceland…

Landhus Farm Barn, Fljótsðalur

Landhus Farm Barn, Fljótsðalur

In this case, the tun is the road itself. It’s the architectural space (within the landscape rather than the farmyard) that carries forth the energy of the tun.

Icelandic Highway 1 in March, Mývatnssveit

Park your car here on the way back home from work.

The word “tun” is the German for “to do”. The English word is “doing.”

A nice triad!

It is a place of energy that creates the economy and trade and activity of a country (or a farm), or lets it efficiently take place. It is the place where the future is created. Without it, the activities of humans would not be as organized as it is, nor could it be efficiently packed up and exported from the farm (or the country.) Iceland, of course, is a sophisticated modern country, so we can expect this source of energy to take many forms today. Here are a few:

Parking Strip.

Art Project in Downtown Reykjavik

Art Project in Downtown Reykjavik

The pattern of tun-in-the-pasture is reversed to pasture-in-the-tun. (The tun is Reykjavik.) This pasture, though, is in the shape of a disused turf house. Clever stuff!

Movie theatre.

The Reykjavik Movie Theatre is Also a Place of Exchange.

The Reykjavik Movie Theatre is Also a Place of Exchange.

Note that this is a re-purposed building. In other words, not only is the movie theatre a contemporary tun, but the building acts as one as well.

Church.

A very useful tun for work with souls. In this case, the houses of the village take the place of the buildings of a farmyard.

Forest.

Summerhouse in Kirkjubærjarklaustur

Summerhouse in Kirkjubærjarklaustur

The trees are part of a nation building program of the Icelandic government. They represent not only shelter and beauty, but future money in the bank. In this sense, they operate as a dung heap in a tun. The land itself has been separated from itself into a special tun space here. Here’s something different…

Youth.

This tun represents a combined cognitive, social and bodily space. It moves around and around through Reykjavik, invading people’s dreams and re-shaping them into effervescent images of mineral water. Not into the dance scene? No problem…

Icelandic Farmstead.

Note the elf house in the foreground. It’s good to live close to your neighbours.

From the perspective of a capital economy, this capital has depreciated to the point of needing to be replaced with a new depreciation sequence paid for with interest. In a tun-based economy, the expense of taking wealth from the land in order to build structures upon it is a debt that will be erased only when the creative (tun-ish) potential given from the land and embodied in the building and the tractor are mined dry and these materials (dung-wise) rot back into the earth. They are, in other words, a fertilizer. You don’t paint fertilizer. You also don’t throw it away. Want something more adventuresome? Iceland has that too.

Svinafellsjokul, Skaftafell National Park

A glacier is part of the common wealth of a country, that which belongs to all of the people and brings water and energy to all. It’s not just the people, either. It also brings energy to the land itself. Here, you can see what that looks like, on the other side of the glaciers.

Strutfoss

Aka glacier turning into light. Very good for the soul.

A glacier can attract tourists (and mine them for wealth), provide healthy recreation for the people (an idea of nature, imported from coal-smoke-choked industrial England), provide habit for fish …

The Laugarfljót, with a view to Snæfells

These are both tun spaces. The mountain generates snow, which generates water. The lake collects the water, to provide habitat for fish. By concentrating energy in this way, mountain and lake make it available for human harvest. (Not that this is their plan.)

Unfortunately, capital-intensive economic systems can mess with that and simplify the idea of a tun almost to unrecognizability, like this:

This is propaganda in the service of art.

This is propaganda in the service of art.

Or art in the service of propaganda. Or a statue in the middle of a hydroelectric dam outflow channel that has diverted the water from Snæfells into the wrong fjord. Something like that. Here, here’s another look:  See that? The ship steams upriver, loaded with generic manufactured goods, towards the economy created by turning Snæfells’ life-giving properties into cash, that can pay for electric toasters and Swedish toilet paper. It never, of course, arrives. Here’s it’s goal…

See that? The ship steams upriver, loaded with generic manufactured goods, towards the economy created by turning Snæfells’ life-giving properties into cash, that can pay for electric toasters and Swedish toilet paper. It never, of course, arrives. Here’s it’s goal…

The Heart of the Mountain

The statue was erected on the notion of eternal wealth, just before the economic collapse made the whole notion questionable. Here’s a construction site (abandoned) in Reykjavik, based upon the economic version of this dam …

OK, So Maybe Not Such a Great Idea After All

If you get too abstract with your tun, you run the risk of running out of manure. Good to know.

Ah, perhaps you’re tired of farms by now? Well, here you go, way up in the north…

A Sea-Going Tun Space

Powered by human energy (doing). Any fish brought into the boat (the tun) are instantly converted into wealth. Well, as long as your arms are strong and the weather holds.

This particular moveable tun has been sitting on the shore for a long time, but the principle still holds. When you start powering that boat with diesel, then a good chunk of the fish you bring in are not wealth, but payment for an operating debt, and, if you bought the boat on credit, a capital debt as well. If you’re not careful, the whole thing becomes a debt. Instead of organizing the wealth of your labour on the sea (very wet common space) for delivery to social space, the tun organizes social relationships for delivery to you. You have, in other words, lost your tun (doing.) Here’s a solution:

Garden.

The Akureyri Botanical Garden

This garden is planted in Iceland’s northern capital to see what plants will grow in a cold, northern climate. The concentration is on decorative plants. That is part of Icelandic nationalism, a way of dunging the country so that it brings forth wealth (in the sense of a tun economy, organized around human relationships to common space (land and water, mostly), beauty and fecundity are both forms of wealth.) So is this:

School.

Hotel Edda, Akureyri

In the summer, the richly-endowed residential high schools of Iceland are converted into hotels, serving travellers. This doing (tun) allows for them to be sheltered and fed without capital-intensive infrastructure on the land, that would not turn a profit (dung) and would be a drain on the community (a kind of field.) In other words, without the Hotel Edda concept, travel in Iceland would be greatly reduced. That is pure tun! In the winter, the schools are tuns of a different kind, gathering Icelandic youth together for their common education. It would be best, however, not to think of these multi-use spaces as either schools or hotels, but as a space which allows for and serves both relationships to the land. See? Pure tun! Similarly…

N1 Gas Station in Blondüos

In sparcely-populated Iceland, a gas station is like a city in itself (Icelandic Staður, German Stadt [city] or Staat [country], English State, and in land terms a Stead, as in a farmstead. Here it’s a gas stead.) Everyone stops (where else?). Everyone eats (hamburgers, chicken, pizza and hot dogs, the national dishes of Iceland, and for the lucky soul a liquorice ice cream bar [available only in Iceland] if you root around long enough in the freezer.) The places so interrupt the roads in a tun-ish kind of way that even the police stop here. Rather than waiting at the side of the road trying to nab people of interest, they just hang out at the N1 and interrogate people while they’re filling up with gas.

Here’s a somewhat more esoteric tun from Kirkjubærjarklaustur:

A Window on the Tun …

… is part of the function of the tun, even when it’s a bit wonky from a stone cast up by a weed eater or, perhaps (judging from the repaired state of the wall) earthquake.

Similarly, a piece of propaganda-art (or is it art-propaganda?) in downtown Reykjavik provides an anchor point for tourists wandering down to the waterfront (very tun-ish, that)…

Leif the Lucky’s Aluminum Ship, with Modern Adventurers

If I was crossing the North Atlantic in a longboat, I’d want it to be a made out of aluminum, too.

… while reminding the Reykjavikers that the money that built their glittering waterfront…

City.

Reykjavik: Iceland’s Tun

It interacts with other national tuns to create the worldwide tun network.

… came from the aluminum smelter (and glacial-melt electricity) across the mountain in Whale Fjord.

Smelter.

Aluminum Smelter with World War II Airstrip (aka bird sanctuary), Hvalfjörður

Leif’s ship points straight this way. This is a capital tun. That it needs space (Iceland) is rather incidental. It might have been British Columbia. Oh, wait, they’ve dammed rivers and diverted them through tunnels and extirpated salmon for an aluminum smelter in British Columbia, too! Like tuns, capital is everywhere. Sometimes it flows right through a tun and obliterates it.

Here’s Reykjavik’s most interesting tun, right on the waterfront …

Harpa

The Reykjavik opera house and performance centre. It also houses a CD shop, a cafe, exhibition space, practice space for dancers, fashion shows and classical, folk and rock concerts. In other words, it provides a space for the concentration of cultural activity of all kinds in sufficient quantity and quality that it can be delivered to the people, the country, and the world. It’s also a beautiful piece of architecture that captures the sun light and casts it in coloured rectangles on the concrete plaza at its base, like sketchings made out of chalk. Tun all the way.

Not all tuns are so complex. Here’s one of the most basic (and powerful) of them all…

Graveyard.

Right Between Church and House

Note the road that comes directly to it. The tithes that came to a church accrued to the landowner who had built the tun space for the people and were, as such, a major form of wealth for Icelandic farms. The byproduct was the dead, who were planted in the tun — a kind of social dung, fertilizing the future (Heaven) or the present (built as it is on human memory, the more the memory the richer the present.)

In this conception of wealth, capital (and money) aren’t exactly the goal, but a product of the tun space. The carefully-bounded space below, on the other hand, added to the tun space…

Field.

Without the line that bounds this field, there would be no inputs to a tun space. It would only be a potential space. Never underestimate a line, in Iceland or anywhere else.

Here, this image may illustrate that more dramatically. Here we are at Myvatn…

Volcanic Slag, fenced and dunged = Field = Horse

Simple math.

If we lift the camera just a teensy bit, we get some perspective…

Volcanic Slag + Capital + Cleverness = Geothermal Power

Our horse is behind the rock.

You see how that works? The land has potential. It has a form of potential energy. The application of a particular technological approach towards defining it as space allows for different forms of energy to come out of it. A line gives us a field, gives us a horse. It will be brought into a tun, where this elementary relationship is retained. Capital gives use geothermal power station. It will be brought into a city, where it’s own elementary relationships are retained. In the first case, the earth is full of life and living relationships. In the second, humans are separated from the earth, which is a field of energy, that can be harvested. The interrelationship between these two ways of being is complex, but at all times the elementary principle remains: creativity comes from the space that is outlined by technology; the outcomes are predetermined. In other words, we who are humans are not separate from technology and cannot just direct it to our will. All we can hope for is to create spaces, which create energy flows that lead to where we wish to go, but we should be very clear as to where they might lead. Here’s a kind of tun that got its start in Iceland over a thousand years ago:

Thing.

The Thing Place in Þingvællir

The world’s first parliament convened on this spot at the confluence of the walking trails of Iceland in the year 930. All the people came and collectively decided their social arrangements, then followed the trails back to their home farms. This is the tun of tuns.

On the principal that space creates function and energy is latent in the land, some tuns are geographical spaces. Like this…

Fjord.

Arnarfjörður, from Hrafnseyrie

This was the view that Jon Sigurdson, father of Icelandic independence, took in as a child.

Here’s a slightly altered version:

Harbour.

Stikkishólmur Harbour

Here’s an example of a common Icelandic tun: a ruin of a lost farm. The people of Reykjavik come from places like this that were no longer tenable in a capital-fueled society. They do, however, remain.

Ruin.

Ruined Farmhouse near Arnarstapi

The mistake should not be made, despite the astute and chilling observations of Iceland’s Nobel Laureate, Halldór Laxness, that such buildings were a betrayal of the debt of humans to their land, as they were too capital intensive and not constructed within the flow of seasons and fate. Instead, it’s better to think of them as graveyards and memory artefacts, that continue to bind people to the land, although only in potential, and offer the chance of return. The energy that was squandered (as Laxness saw it) on these buildings, remains in them, as it also remains in the land, and can be mined again. Only in the sense of capital is it lost.

Well, there are many other forms of doings in Iceland. Cataloguing them won’t add to that appreciably. But perhaps this image might sum it up:

Bridge.

Like the string that defines a field and allows for concentrated activity, a bridge is another technology both similar to a tun and connected to its energy. It allows for improved delivery of material to the tun, without the contamination of important water sources with the mud generated by foot traffic. In this case, perhaps not so well, but, hey, I used this bridge on my way to the Dwarf Church in Seyðisfjörður, and it did its thing. Oh, and as for bridges, here’s one…

Like the string that defines a field and allows for concentrated activity, a bridge is another technology both similar to a tun and connected to its energy. It allows for improved delivery of material to the tun, without the contamination of important water sources with the mud generated by foot traffic. In this case, perhaps not so well, but, hey, I used this bridge on my way to the Dwarf Church in Seyðisfjörður, and it did its thing. Oh, and as for bridges, here’s one…

Golf Course.

Slowly, a people who have lost their connection to tun space are refinding it, in the golf course surrounding a church which was set up next to an elf city in the lava fields south of Reykjavik. Humans are like horses in a field. They really can’t wander that far.

Slowly, a people who have lost their connection to tun space are refinding it, in the golf course surrounding a church which was set up next to an elf city in the lava fields south of Reykjavik. Humans are like horses in a field. They really can’t wander that far.