Well, not trolls exactly. And not exactly a house. It’s a bit of a riddle, but poets love riddles. Why, you could even say that on the northern shores of the world, poetry developed out of riddles, or that skaldic poetry did, at any rate. Here’s a famous Icelandic skald:

Egil Skallagrímsson, Skald

Ready to do battle with, what’s that, a rusty sword? More like a cleaver, I think. I have used things like that to pick cabbages. Poet farmers unite! (17th Century Manuscript from the Árni Magnússon Institute).

A scaldic poem is a ceremonial poem, given as a gift by a poet (a skald) to his patron, written in praise (or at times rousing criticism — very scalding, very scolding criticism). Scaldic poetry was worked through in intricate design and was intended as a verbal form of the intertwined patterning on a shield — a kind of protective magic. (The contemporary equivalent might be depleted uranium.) At times, skaldic poems were even recited before battle. They were part of the battle. An important part, too, that preceded the bloodiness.

The Karlevi Stone, Vickleby, Sweden

Photo by Berig.

Note the vertical columns of the scaldic poem above. As Gunnar Gunnarsson pointed out in Unser Land (the speech he read from during his 1940 literary tour of Germany), they are not much different than this:

Basalt Columns, Vík í Mýrdal

A tightly-linked protective shield poem against the encroaching sea, written in the land itself. (Note: studies from Hawaii have shown that black basalt beaches like this form in hours, not centuries.)

Isn’t that cool? A poem that is the land? That is the riddle Gunnarsson was speaking from: his house is Iceland; Iceland is his house. If that sounds a little unusual, do recall: he’s a poet; he’s not really thinking in metaphor. Mostly, metaphor is for people who are not poets. It’s a useful way, for sure, of describing the work of poets, but it does do so without really accepting the poem as the reality of the world, which is the poet’s way. In the case of Gunnarsson’s house and island, that work is performed in skaldic poetry, which makes his house a shield as well — and not just a shield, but an ornament, too, like this, maybe:

Viking Broach, Sweden

Men might have wanted shields, to protect their bodies in battle, but, perhaps, just perhaps, women wanted something to hold their garments together at the shoulder, something that was as protective as a shield, something with an island in the centre and the four points of the compass around them, something that would set them at the middle of the world. In Sweden’s case, that would have been North for the Trail to the North (Nor’way), South for Denmark and the trails down the Rhine, East for Finland, and West for the Orkneys — and if you just kept going, going, going, going (whew) … aha! In the middle of the ocean… Iceland.

Once people arrived in the middle of the North Atlantic, the compass shifted. Iceland was now at the centre of the world. The other points of the compass were adjusted accordingly, to reference it. Since all directions led to water, however, Iceland became the entire earth, floating in the universe (which was a big, cold sea). The country is still roughly divided into these quadrants.

Iceland, the Compass Version

The shield and compass pattern extends beyond maps. For example, if you really wanted to get into the whole magical side of things, and weren’t squeamish about a little darkness in your life, you could play around with something like the following (You could even write it in your own blood):

Vegvisir

An Icelandic magical stave. Staves come in many shapes and were drawn for many different purposes.This one is a compass written in magical symbols, and was used to find one’s way in bad weather.

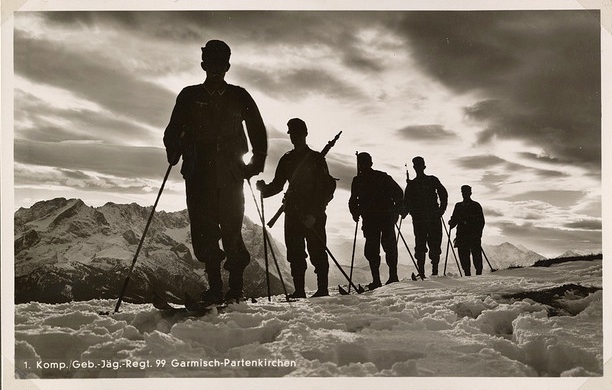

For such a stave to work (if it did), such navigation would not be done by the physical properties of the land, but by spiritual ones — and we’re not talking Christian-spiritual. In the high days of the Christian Church in Iceland, the possession of such staves could have had you condemned as a witch and beheaded at Þingvellir. That might have been awfully un-Christian, too, but, still, even today, this kind of magic is not advisable. When the Germans tried this kind of thing in the 1930s, for one thing, they invented the 1940s, which turned out to be a really bad idea.

Dresden, February 1944

Among the 20,000 people killed in the Allied bombing of Dresden and the millions of German refugees who streamed through it shortly afterwards on their way south and west from the Baltic, were untold numbers of readers of Gunnar Gunnarsson’s books about Iceland.

The pattern of land-as-compass-as-shield continues further, into practical applications of gentler spiritual principles. This time, they are placed in the interests of nationalism, where it’s not black magicians in the West Fjords or Ancient Viking ancestors or ultra-Nationalist Germans trained in the killing fields of The Chemins des Dames who are leading the way to a nation, but young women, quietly fitting their minds to the old patterns, to create a little beauty and order out of the blank, snow-white flaxen cloth woven out of the country’s fields. Think of these as self portraits…

Icelandic Needlepoint Pattern

Flowers, yes, but also a hand-held mirror lifted from a dressing table, as well as the old compass, the old shield, the old broach, and the old skaldic poetry, too. Not to mention Gunnarsson’s house. Yes, the house. Such a pretty thing. Such devotion.

If you think I’m stretching this, consider that five centuries ago in the cloister below Gunnarsson’s house at Skriðuklaustur illiterate young women would have made embroidery of the flowers of the fields. It was a form of prayer, practiced between caring for the sick. Such devotion was the unique Icelandic contribution to prayerful attention and worship, in the way that the repetitive painting of icons of saints was an essential contribution to worship in Russia.

Christ Pantokrator

6th century encaustic icon from Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai. The power comes from about fifty coats of paint and the deliberately non-representational nature of the image. God, after all, can’t be reproduced in an image, so trying would be arrogance. Accordingly, such images aren’t representations of God. They are God’s presence, revealed when people devote themselves to old patterns.

The repetition and patterning were key. For example, just down the valley from Gunnarsson’s house at Skriðuklaustur, the old girls’ school at Hallormsstaður trained girls in Icelandic embroidery, as one part of a project to create a culture in Iceland independent from Danish influence. If the home was the heart of the country, and women were at the heart of the home, and the country was its children, then Icelandifying young women would, it seems, pay future dividends. Politification (My, aren’t I inventing words today) of national identity could follow at its own pace.

Icelandic Nationalist Embroidery, 1930s, Hallormsstaður.

The doors of the rooms in the school dormitory bear the names of trees, instead of numbers, and are set within a somewhat overgrown botanical garden. Such gardens were decorative in mainland Europe. In Iceland, they are a more practical magic.

The embroidery above is much like a map of Iceland. When you get down to ground level, after all, and experience the map that is Iceland on a human scale rather than an international or global one of contours, nation states, trade patterns, colonies, weather isobars and even corporate banking, Iceland does look like this:

Iceland at Ground Level, Neskaupstaður

The embroidery of summer!

This beautiful meadow, may I remind you, is still our shield and still our skaldic poem. It’s also Gunnarsson’s house, his novels, and the workings of his subconscious and conscious minds. Skaldic poems are full of doubling like that. We’re back to this:

His house is Iceland.

Iceland is his house.

Very skaldic, indeed. Of course, in physical terms, when this skaldic play comes to Gunnarsson’s house, the whole thing does look awfully German.

Skriðuklaustur

The German architect, the Icelandic stone, the grass roof…why, it’s an island itself. An island in itself. An island. Itself. German….German? That’s the riddle within the riddle.

The poems are our key. The first form of doubling in a skaldic poem is a kenning. Kennings are natural word forms inherent in Germanic languages (Frisian, Icelandic, Norse, English, Danish, and so on). Speakers of these languages use words like that all the time. Some English examples are: butternut, windowsill, firefly, and doublespeak. In kennings, this tendency is made artful. Each kenning is a miniature poem in itself. Take the land, for instance, such as that forming Iceland. Take a look at the series of kenning’s below. The earth is cleverly hidden with them, or perhaps cleverly revealed. The delight in recognition is part of the magic of the poem. Can you find the earth there, in its sea? (The translation [mine] is loose, to try to catch some of the music, but it’s not wildly off track, or at least not enough to hide the earth any more than it already is.)

Skaldic Poem Made Out of Kennings

The earth is “The sun’s stronghold”. The others? Well, hey, it’s a riddle, right? Source.

So, that’s the first doubling: words are given multiple meanings by being joined together. In the example above, the earth is both rock and stone as well as “The sun’s stronghold” (as opposed, seemingly, to the darkness of death, underground, and the land of the salmon, or water). The other doubling comes about because the rhyme schemes of these poems were so intricate that the poem often had to be split in two columns, one representing each of its two speakers. Two speakers? Yes, that is another old Nordic style of poetry. Here’s what it looked like in its Finnish variant…

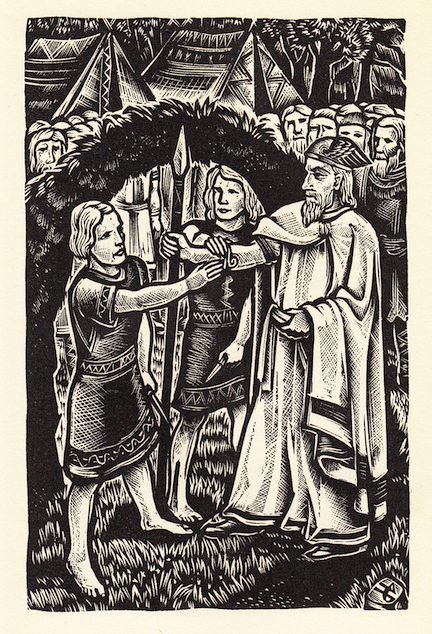

Finnish Folk Singers, Telling a Song Together

Each singer pulls the other towards himself to speak, then follows the other to listen, to pull again. It’s like rowing, or weaving.

Such poems looked like this, sometimes (the first line in each rhyming pair was given by one speaker; the second by the other… a pleasant game, for sure):

The Kalevala, Canto 27 (Opening)

Finnish is related to Pictish (and nothing else), the language of Scotland before the Vikings took the place for their own.

Here it is again, in English from the time of Gunnarsson’s youth. This time, the rhyming pairs are bound on single lines (to draw parallels with Homer, by the sounds of it):

The Kalevala, Canto 27 (Opening)

The Kalevala, Canto 27 (Opening)

Finnish folk poetry, compiled and massaged into a narrative by Elias Lönnrot. Translated by Frances Peabody Magoun, Jr. Homer was extensively read in literary circles at the time.

Two speakers. That’s the key here. But who are they? Ah, they are many things, many of which I have already hinted at here: Iceland and Germany, Gunnarsson and Denmark, Elves and the Church, earth and language, men and women, peace and war, individual and state, man and God. It looks like many things, but that’s just a linguistic convention. It’s really all part of the same conversation — if those words could be brought together into one tightly compressed thing, we would have Gunnarsson’s house. Let’s not forget that Gunnarsson was an Icelander. For a man like him, the word ‘thing’ has special significance, and looks like this:

þingvellir, the Thing Place

Iceland’s first thing, or speaking (In Icelandic, Alþingi. In Norman English parliament), took place here in the Mid-Atlantic Rift in 930. In 1000, the country chose Christianity here, for practical reasons to do with unity, self-determination and self defense.

Below the Icelandic flag above, there is a church, and a curious collection of houses…

þingvellir Church, 1850

The earliest church on this site dates from the early 11th century. The row of five houses to the right of the church represent the Icelandic state. Each time the constitution has been rebuilt from the ground up, a new house has been added to the row. The one house that is not represented here, is the one in Fljotsðalur to the North East. That’s right: Gunnarsson’s. Hey, no one said he was particularly modest. The volcano, Thor’s Shield, rises faintly in the background, from the earth’s core.

I was standing down by the church, looking up at the Alþingi site and wondering why it was placed here, of all places. Official documents point out that it was on a list of four possible sites, and was chosen because of the four it was the one situated conveniently on the country’s major trade routes (horse paths), and had sufficient pasture, water and wood (for fires) to sustain a large crowd. Makes sense. But why was it on the list in the first place? I wondered, then I got to daydreaming, as poets sometimes do, and thought about being a kid back then, attending the Thing with my family, and I looked up at the cliffs and they came into focus.

A troll!

Another troll!

Another troll!

Yet Another!

Yet Another!

Trolls Everywhere!

And all of them are looking down over the people. You could say that the land is taking part in the discussion that is taking part in the Thing. You could say that now the past is watching the present, and looking down over the house that is Iceland, which is embedded in that past. Time and space are unique here. They are a language. Since that’s an unusual language, at least for the contemporary, novel-driven world, it’s useful to walk through its halls a bit, to see how they’re constructed and where they lead. I’ll do that in the next post. We’ll walk among elves and dwarves and trolls. They are not part of fairy tale. They are something completely different, and provide clues to the mind of Gunnar Gunnarsson in 1940. It’ll be fun. I hope you’ll come along.

… I felt that I was winding life on the axle of the universe or the pole of the earth, day by day by day, that with each twist of the birch twig to accept the string, a year passed, and I felt life in that string, not just the life the wind gave it, but energy from the universe; I felt that I was weaving with an ancient craft, in a small physical prayer, from the well up to … well, let’s just say Mary, who after all, was a spiritual fire in a human form, until all that energy was there, wound up on its spindle, at her feet …

… I felt that I was winding life on the axle of the universe or the pole of the earth, day by day by day, that with each twist of the birch twig to accept the string, a year passed, and I felt life in that string, not just the life the wind gave it, but energy from the universe; I felt that I was weaving with an ancient craft, in a small physical prayer, from the well up to … well, let’s just say Mary, who after all, was a spiritual fire in a human form, until all that energy was there, wound up on its spindle, at her feet … … (and the steam from my potatoes), waiting for me to think some more, in this fashion of thinking that is not done with words but with the body and in the world. Poetry had its roots there. I have learned here that it has not left them. For me, that stone is not the same.

… (and the steam from my potatoes), waiting for me to think some more, in this fashion of thinking that is not done with words but with the body and in the world. Poetry had its roots there. I have learned here that it has not left them. For me, that stone is not the same.