Today, I praise the rowan tree. This is her season, as ice breaks to the season of water and birds.

Rowans with Elf Stone, Eyjafjörðursveit, Ísland

She’s a tree, yes, but look how she wants to lie on the ground. None of the towering heights for her.

Rowan, Skriðuklaustur, Ísland

And when the light comes, ah, then she is a torch.

Good Friday Rowan, Valpjofstaður, Ísland

The Rowan is sacred to Brigid, Saint of Holy Ireland, and to Bride (or Brigid), who came before her (and was no saint), and to Mary, Mother of Christ, and to Thor, god of lightning and thunder. The gender crossover is no big thing. Don’t give it a second’s thought. There was a time on earth when all things that signified the earth’s power most strongly were considered hermaphroditic, neither male nor female, and, after all, don’t humans, who come in several genders, tend to unite and make unions that are neither but are one?

Male and Female Fruit From a Hermaphroditic Pacific Mountain Ash

Wells, British Columbia

Unlike those sly sumacs and gingkos, a rowan has neither male nor female trees.She knows where she is. Look at her, earth tree, reaching up for the spring moon, with her feet planted firmly on the ground.

Skjaldarvik, Ísland

Wherever a rowan is found, it signifies the presence of her deities, who might have many names but are also one.

Thor, Brigid, Bride

For all of you who are of an empirical bent, don’t worry. Gods are just names for powers of the earth. The powers are present, even without the names, although perhaps not yet empirically defined. It’s just a kind of short hand. For those of you who follow the stories of the gods and goddesses, you know what I don’t have to say.

Rowan in the Birthplace of the Gods, Ásbyrgi, Ísland

Much of (nearly treeless) Iceland was one treed like this: a few rowans, and a lot of willows and birches. Then people got cold.

There’s more to the story of the rowan than is written down in history books, but not more than meets the eye. A lot of it has to do with environmental sustainability. A lot of it has to do with her name: in English, rowan, for red; in German, Eberasche, or red ash, or, more precisely, “red spear”. More on the spears in a sec. First, here she is, surprising us and all.

Pacific Mountain Ash, Quesnel Forks, British Columbia

Mountain Ash, Rowan, Eberesche, Bird Berry, Thrush Berry, Sorbier, well, you get the idea: a rose all dressed up.

She is glorious in summer, but look at her in her winter time, just last week…

Rowan has a profound story. Don’t look for it on Google, though. This is one you have to learn from the birds.

Yes, Today the Cedar Waxwings Have Come Back Home to the Rowans! Yay!

The story of rowans is a story of sacrifice, androgyny, magic, Christianity, nationalism, survival, life and hope — always hope. It is also one of the oldest stories of all. It begins with a Himalayan god of the air, Thor. He’s known today as a Nordic god, from Iceland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Germany at the north of the world, but he started out far to the east and south, and migrated with his believers across the continent. Thor has a hammer, that’s sometimes an axe, and, as you can see below, blood spatter, a phallic spear, and a weird right hand, and, yes, he’s been repainted with good old-fashioned wheelbarrow paint.

Thor at Lilla Flyhov, Sweden (c. 1000 – 1500 BC) Source

That blood spatter? Well, look:

Rowan Berries in the Snow

They don’t call these bird berries for nothing!

That weird right hand? Here:

Rowan Berry Cluster After the Feast

And that axe? Well, Thor, remember, is a thunder god, from a time when thunder and lightning were the same thing. This is where he lives:

Dragon Tales in the Sky

People used to be able to read this language. It was a kind of writing not in words.

Thor used the axe to split that sky apart, so that out of its unity came lightning (on the one hand) and thunder (on the other). That is the moment in which consciousness is born. Into this air, that is all one (and out of which thunder and lightning come)…

… a spear …

Rowans Were Traditionally Used to Make Spear Shafts

… is thrust. It’s a curious kind of spear…

You wouldn’t want to thrust something like that at a wild boar or something. I mean, how pointless (literally). Sure, if you’re thinking of weapons being physical things, with pointy sharp bits, ya, but weapons are also extensions of the mind, and for Thor, and people who believe in him, this is mind, given body in the world…

You might want to have that magic and balance on your side when you go out to stick a wild pig that’s intent on sticking you (especially if you have the other kind of spear from the other, straighter, kind of ash (spear) tree. The darned things grow in thickets, ready made. You just need an axe to cut one from the ground and you have a weapon that extends your range and does your will at a safe distance from your body. A rowan spear, though? It’s both the thrust and the moment of reception, which is to say that it is a kind of symbolism or visioning, which practitioners call magic. Look how the boar’s blood and the spear are both present at once, and how the weight of the blood lowers the spear.

The tree is the embodiment of action. The mountain ash doesn’t make a great spear, but it certainly is a great way of focussing mind and body on the act of spearing.

There is, however, another angle to this story (as there always is in the world of indigenous thought and the language that speaks it best, poetry.) The red blood is the blood of a victim, the blood of a virgin, menstrual blood, and both life and death in one. Thor of Lilla Flyhov said it perhaps as simply as it needs to be said: the spear and a phallus are one. It thrusts upward, pierces the belly of the sky, and rains blood

Wells, British Columbia

Sacrifice and birth, male and female, action and reaction, in one representation: this is Thor’s presence, the concept of creating action out of stillness and seeing in stillness the potential for action. It is consciousness, for sure, but it’s also the body. Look again at that weird right hand.

It’s a placenta. The tree has many of them. It bursts out into them all over.

The tree has many of them. It bursts out into them all over.  The rowan is drenched in the blood of life and death. It is Bride and Groom, or Thor, in one. He cleaves unity to bring it together in a different form. This is the ladder one climbs to the stars.

The rowan is drenched in the blood of life and death. It is Bride and Groom, or Thor, in one. He cleaves unity to bring it together in a different form. This is the ladder one climbs to the stars. I hope those of you reading this post for science aren’t scratching your heads at all this poetry and wondering when the science is coming. It’s coming. It’s just that this poetry thing, well, that was science once. I don’t mean bad science, full of childish explanations of the root of physical processes, the ones that science has done such an amazing job of parsing, or cutting part, after Thor. I mean, poetry’s way of finding correlations and moments of doubling, uniting seeming opposites or creating them out of thin air, applied to the world, is a powerful tool for understanding it and for manipulating it — not through manipulating its physical stuff, as contemporary applied science does, but through manipulating the minds of the people acting and living within it, and changing the earth through that energy. I know so many scientists with such deep concern for the earth, all looking for a way to bring their message across and effect meaningful change. Poetry, written out of the earth and with the language of the earth and human bodies, has always been able to do that. The other kind of poetry, the one written with words on a page, can do it among people highly trained to cast their selves within books and to bring back, so to speak, the fish of thought, but it’s not completely the same thing, and might just be the reaction to a passing technology. The thing about these sky gods, though, like Thor, is that they are embodiments of a central knot within hunting, butchering, and its ritual form, sacrifice: the act of killing in order to bring life. Thor’s not the only one. Christ stands in this tradition. The god Mithras, who also came from the East, and whose cult very nearly won Rome over in place of Christianity, was one. With his dagger, he slayed the sacred bull and created the universe. We are sprung from the drops of the bull’s blood.

I hope those of you reading this post for science aren’t scratching your heads at all this poetry and wondering when the science is coming. It’s coming. It’s just that this poetry thing, well, that was science once. I don’t mean bad science, full of childish explanations of the root of physical processes, the ones that science has done such an amazing job of parsing, or cutting part, after Thor. I mean, poetry’s way of finding correlations and moments of doubling, uniting seeming opposites or creating them out of thin air, applied to the world, is a powerful tool for understanding it and for manipulating it — not through manipulating its physical stuff, as contemporary applied science does, but through manipulating the minds of the people acting and living within it, and changing the earth through that energy. I know so many scientists with such deep concern for the earth, all looking for a way to bring their message across and effect meaningful change. Poetry, written out of the earth and with the language of the earth and human bodies, has always been able to do that. The other kind of poetry, the one written with words on a page, can do it among people highly trained to cast their selves within books and to bring back, so to speak, the fish of thought, but it’s not completely the same thing, and might just be the reaction to a passing technology. The thing about these sky gods, though, like Thor, is that they are embodiments of a central knot within hunting, butchering, and its ritual form, sacrifice: the act of killing in order to bring life. Thor’s not the only one. Christ stands in this tradition. The god Mithras, who also came from the East, and whose cult very nearly won Rome over in place of Christianity, was one. With his dagger, he slayed the sacred bull and created the universe. We are sprung from the drops of the bull’s blood.

And, like Thor, he had an axe (and a dagger, which is kind of a short spear, but does the trick.)

And, like Thor, he had an axe (and a dagger, which is kind of a short spear, but does the trick.)

Mithras Killing and Creating

Mithras Killing and Creating

Relief from Heidelberg-Neuenheim, Germany, 2nd Century AD Source These placentas, though. That’s where Bride comes in, the Goddess. If the spear is androgynous, and holds in time both the fertilizing thrust of a phallus and the blood quickening in a placenta, then this is as much the goddess’s tree as the god’s. It has that power of transporting one from one state to another, like the Roman god Janus, who was a doorway, that went both ways equally and transported you from one state to another every time you passed through him (and who, dear scientists, wasn’t a god in a simplistic sense but a way of remembering that cognitive power, and focussing it, for what could come from its development), and, more than Janus, of being both states, male and female, killer and victim, at once.

These placentas, though. That’s where Bride comes in, the Goddess. If the spear is androgynous, and holds in time both the fertilizing thrust of a phallus and the blood quickening in a placenta, then this is as much the goddess’s tree as the god’s. It has that power of transporting one from one state to another, like the Roman god Janus, who was a doorway, that went both ways equally and transported you from one state to another every time you passed through him (and who, dear scientists, wasn’t a god in a simplistic sense but a way of remembering that cognitive power, and focussing it, for what could come from its development), and, more than Janus, of being both states, male and female, killer and victim, at once.  It is also, as you can see, drawn to the sky, and bowed down to the earth as a consequence of this grasping, which always ends in feminine fruitfulness. That is a good lesson. Another is how this tree’s lightning bolt shape …

It is also, as you can see, drawn to the sky, and bowed down to the earth as a consequence of this grasping, which always ends in feminine fruitfulness. That is a good lesson. Another is how this tree’s lightning bolt shape … …ends in a flowing (quite the different thing), which is a hand, that has the capability of grasping.

…ends in a flowing (quite the different thing), which is a hand, that has the capability of grasping.

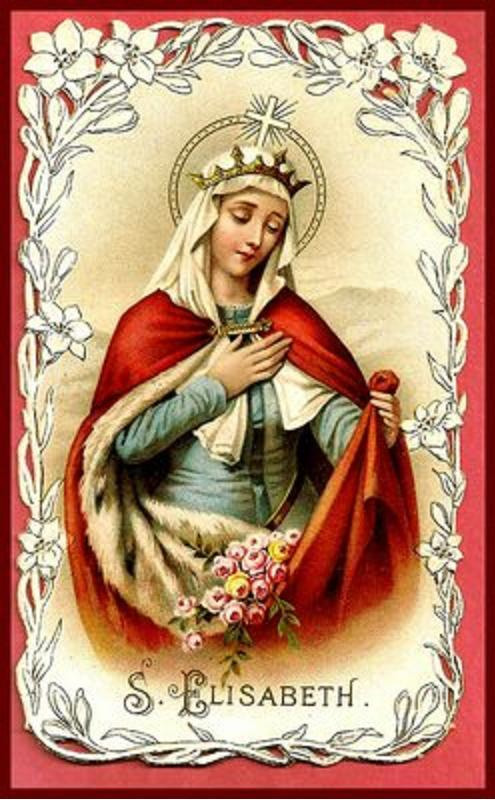

What does it grasp? The easy answer would be that the early church, needing to gain converts from celtic practitioners (the Celts, too, came from the East), simply replaced Bride (or Brigid) the goddess with Brigid, the Saint of Kildare.

Brigid, Saint of Kildare Source

St. Non’s Chapel, St. Davids, Wales

The better answer would be that the Christian shepherd’s staff, and the rowan were recognized as one …

The crook is there, with Christ’s blood, at the intersection of Earth and Heaven, life and death, and Christ cleaves them with his presence and the axe of his love, so to speak. This is no distance at all. The movement to Christianity wasn’t a conversion but an enlightenment, like the scientific Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries, a kind of purification, extension, or manifestation of what was already known.

For this reason as well, rowans were considered an effective charm against witches — not against practitioners of the old arts, but against practitioners who hadn’t moved over to the new understandings of them, finding flower and fruit in the Christian story.

Rowan, Hólar, Ísland

I’ve shown you all these images of Iceland for a reason here, beyond my love of rowans and the beauty of the place. In Iceland, where the trees were all eaten and grazed away, independence from centuries of exploitation and misery under a regime of Danish traders came about through poetry, and the replanting of lost birches and rowans in Iceland. The attempt was to make the country a poem again, to rebuild, so to speak, the first moment of settlement, and reclaim that creative potential and independence. It worked, or at least it helped. Today, Reykjavik is still rich with these nationalist trees …

… that are kind of in the way, but no-one wants to cut down such magic.

… that are kind of in the way, but no-one wants to cut down such magic.

They might try, but they just can’t go through with it. The trees have that much of a hold.

Reykjavik

The churchyards are rich with rowans, too. They signify not only the transfer of energy from pagan to Christian understandings of Thor’s axe and Christ’s Word …

Mårten Eskil Winge’s Thor (1872) Source

Note that cross that Thor is wielding there, the clever lad.

… but the balance struck between them …

Icelandic Stallion Grazing on an Elf Hill Under a Nationalist Agricultural School Churchyard Rowan (Laugar, Ísland)

In Iceland, you throw nothing away, because it is all alive in time. That is the balance, too.

The result is a way of being in balance in the world we live in and the world to come.

The Rowans of the Reykjavik Graveyard

The Rowans of the Reykjavik Graveyard

Graveyards aren’t for the dead. They’re for the living. They focus the mind and so change the world. Every rowan does that …

… not just to those who know its stories, but to all who know how to read its language in the wild. By bringing that into our social structures, we become the world. We become changed, and the world we imagine becomes changed in turn, and so it comes to pass by the action of our hands. The ancients knew this, and worked hard to protect these relationships. For young men, Thor’s axe might have been there to gain advantage by cutting through the wisdom of the world and recreating it as action, but there were large social structures to guide that strength into productive and ultimately feminine forms.

In historical terms, it means that in the lands of the rowan, the Christian staff can be a magical one at the same time, with no contradiction. The rowan’s staff, or bloody spear, has led to such concrete social acts as the creation of states, science, and female power.

I hope you will find a rowan on Brigid’s Day and find your balance by being in its presence —for personal development, if you need that, for spiritual purposes, certainly, and for social development and renewal of the principles embodied in this tree and in the powerful, earth-altering symbolic life to which it has been dedicated.