Today I’d like to walk around within the country shared by Modernist Icelandic Writing and Hamlet, which should be fun. I’m also going to try a little experiment in adapting modernist Icelandic literary method to the journey as it unfolds. First, though, I’d like to introduce you to a literary movement and historical period called the Icelandic Enlightenment. That’s a term I coined this morning, to describe a kind of ongoing clash of worlds that followed hard on the heels of the Celtic Renaissance and the French literary genre Surrealism. It looks a bit like this some days:

Power and Security, Old and New at Landhus Farm

First the sod house, then the enlightened version, the hydroelectric grid, the modernist Icelandic writer Gunnar Gunnarsson, who was raised across the river from this farm, was trying to keep both forms of being in the world both alive.

And now, an apology. I wrote river, but in this valley where the lake is a river and there’s no clear point at which the river becomes the lake that is a river, this part of the river is not a river at all but a Penstock Outrace Canal for East Iceland’s controversial Fljótsdalur hydroelectric power station, so I guess I’d better show that to you, too, and come clean from romance …

The water, you see, descends a couple thousand metres vertically down through a tunnel bored into the mountain, drives the turbines in the power station, pours out here back into the light, and then, ta da …

… into the canal and around this, um, this , ah… well, look …

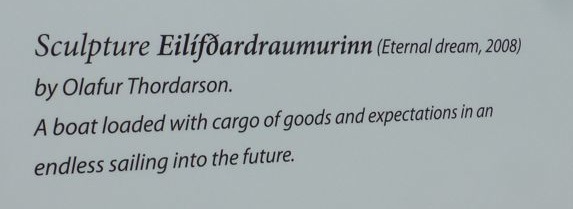

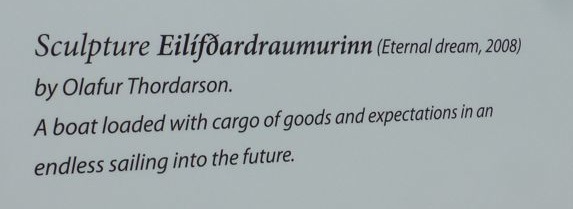

That’s art, that is. A life-sized ship, apparently made out of some approximation of strapping tape plastic-machéd together by techno-sorcery by Olaf Þorðarson, and the whole thing translates into the new Latin, the new commercial trade language of the world, English, like this …

Well, Almost English.

More like German modernist poetry, really, which explored such forms of atomic compression. More like “A boat loaded with cargo-of-“goods-and-expectations” in an endless-sailing-into-the-future. Nice to see the peoples of Northern Europe coming together in such an unexpected spot for a moment together in the sun. Thanks, Olafur!

Well, and all I wanted today was to tell you about Gunnar and the Nazis, because there’s a story for sure …

Gunnar: (Interjecting.) I was no Nazi! I am sick of people coming to my house in the country and calling me a Nazi because the house has grass on the roof, because my friend Fritz designed it and he joined the Party because it was the only way to secure work, because his design blends North-German, Danish and Tyrolean agricultural folk architecture into a statement about a farmer’s house fitting into the land rather than intruding upon it like a, like a … oh, grrrrrr.

Oh, hi, Gunnar.

Gunnar Gunnarsson, Skald

After that imaginary outburst, he is being a bit tight-lipped today.

A secret agent, even beyond death. Clever.

(Gunnar grumbles inaudibly.)

So … well… that silent battle of wills went on for awhile … no need to bore you with that, but, um, let’s face it. That is the kind of silence one gets when one attempts to talk to the dead. To hear Gunnar better, because I really did wish I could have a talk with him, on his own terms, so to speak, I started translating his book “The Northern Kingdom”, and realized, sheesh, power plants and public art notwithstanding, I forgot to set the scene. I mean, “Icelandic Enlightenment”? I reckon if I’m going to throw terms like that around like spring waterfalls split rocks from their cliffs with a sound like artillery fire…

Hengifoss, a High Waterfall just up the Road from Gunnar’s House

Soundtrack: Roar…. BOOOOMMM! …. Roar ….. BOOOOOOOMMMMMM! It’s enough to make one start seeing trolls.

…it would be best to show you what I mean. So, to be a better host, and I do mean to make you feel at home here in my grassy house on its grassy hill nestled into its grassy island of Japanese cars in its cold blue sea, here’s another view of that Enlightenment…

Angels of the Universe, Reykjavik Harbour

None of this old-fashioned monkishness and cloisterly prayer here, I tell you. Actually, I think Gunnar might have liked this. Not the graffiti, though. He would’ve sent a man out there with a bucket of white wash.

So, that was still a bit obscure, darn it, but I’m a writer, just like Gunnar, so, hey, maybe some words will help. Maybe if you could hear a Canadian writer humming and hawing out loud you’d know how things were going with the world today, here in what’s lovingly known as the Northeast, except if you’re on the Faero Islands it’s the Northwest and if you’re on Greenland it’s, um, well…. Oh, bother, we need a writer to sort these things out, that’s what we need. Ah, let me see, yes, here’s that writer, right down the hall here … ah …. yes. Here is is. Um … Harold?

Canadian Writer: (Startling awake from his writerly dreams, or maybe not awake at all.) “The Enlightenment” was the period in 17th and 18th century European history when the human capacity for reason gained cultural ground over the capacity for faith and started to create the scientific world out of a poetic one.

I know, like whew! Get a writer talking and, worse yet, thinking out loud, and words start flapping around like that, and like this, too, I might add …

Black Words in the Lagarfljot…

… flying off to check out the sheep folds at the first sign of a writer pulling a camera out of his pocket.

and like this …

Canadian Writer: It was largely a French, German and English business. It hit Iceland late, in the early twentieth century, in the writings of Gunnar Gunnarsson, composer of semi-autobiographical, poetic, political “novels” that brought poetic forms of Icelandic thought into the light — with one crucial difference: this ‘light’ was modernism, not rationalism, as it had been in the original Enlightenment. Big difference, actually.

Raven 1: Aha! You mean, instead of constructing rational, scientific structures for organizing the world based upon the administrative structures of the French court, as did the philosophers and scientific pioneers of the Enlightenment …

Raven 2: Whee!

Raven 3: What a nice day for flying!

(They fly off looking for some sheep’s entrails to read. Disappointed, the writer puts his camera away.)

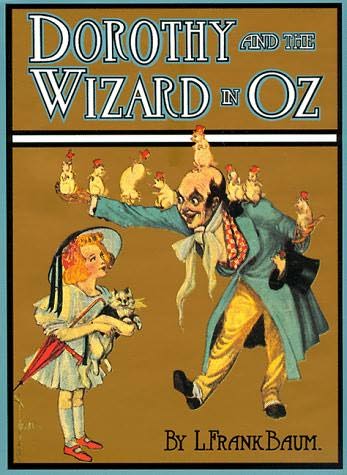

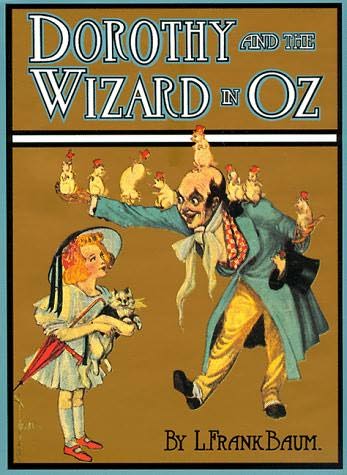

Ah, writers. They’re always wandering off. I guess there’s nothing for it but to continue on bravely without them and hope for the best. As I understand it, denied by the age of his birth the benefits of emerging into a developing culture organized around rational structures, including Science, Mathematics and Engineering, Gunnar was stuck with writing “novels” instead — a kind of intellectual activity that in the post-rational world of his birth and coming of age was most often considered “entertainment” or “fantasy.” Well, actually, most often it was. Yeah. there’s that. Like this 1908 American novel about a girl from a rather hopeless, helpless farm who comes to the, um, big city of, um, God and wins out by her true heart…

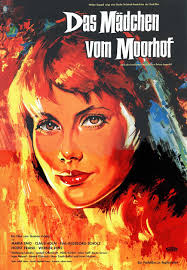

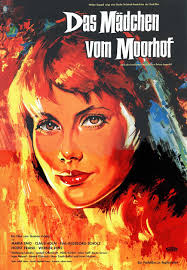

… or this beautiful 1970s German version of the Nobel Prize-Winning 1908 Swedish novel Tösen från Stormyrtorpet (The Lass from the Stormy Croft) about a girl from the isolated poverty of the northern wilderness, who, well, look at the strength in her eyes, eh …

Such was Gunnar’s readership. Not the ideal one for a modernist writer, a man from the Icelandic Enlightenment, but, still, you had to buck up and start somewhere, right, trusting to luck and youth and hope? You most certainly did.

The Hopefully Uncertain Young Gunnar

With his big Scandinavian farmer’s hands, newly-planted in Denmark. I don’t know about you, but does it, um, look like his pupils have been inked in by a photographer cursed with red-eye?

Fortunately for Gunnar, it was a foundation stone of modernism (and its revolutionary and energizing core) that these entertaining objects could have political and economic ends, if a man (seemingly, men did this kind of thing) put his mind to it — and it was this that Gunnar was counting on. His contemporary, the American Ezra Pound, was as well. Pound, who was a gifted lyrical poet, was pushed by the catastrophe of the First World War to write stuff like this:

The first thing for a man to think of when proposing an economic system is;

WHAT IS IT FOR? And the answer is: to make sure that the whole people shall be

able to eat (in a healthy manner), to be housed (decently) and be clothed (in a

way adequate to the climate).

Ezra Pound, "What is Money For"

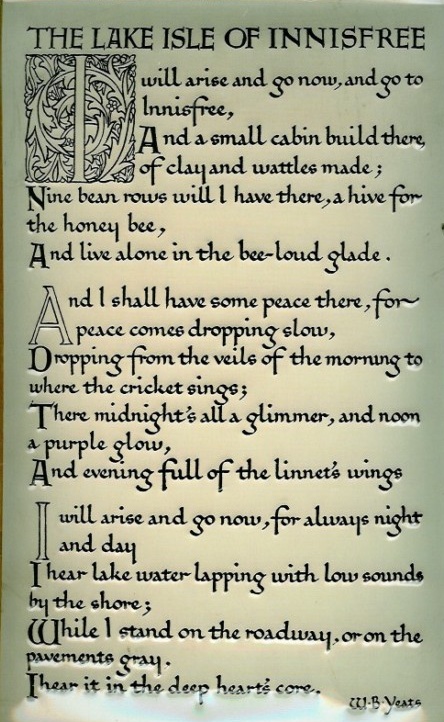

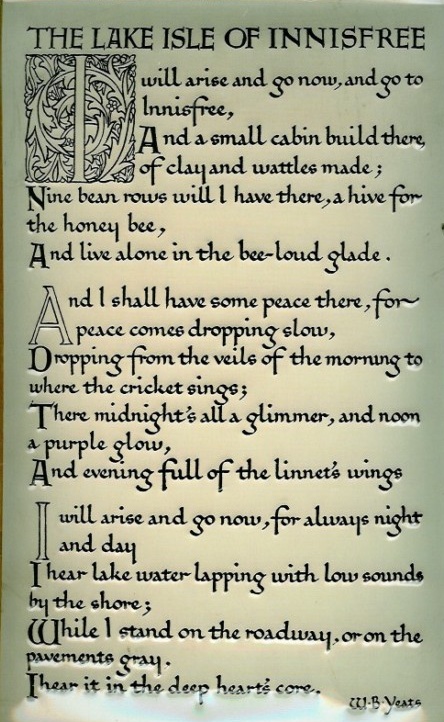

A Very Upper Middle Class English Sentiment, but then, Pound had spent the War in England, and the decade before it, too, where he had gone to discuss Fairyland and the Celtic Renaissance with the poet W.B. Yeats, and had married into this class. I trust you see the pattern …

Yeats’ Dreamy Romantic Fairyland: an Unlikely Start for Ultra-Modernist Poetics

OK, Ireland is not exactly Scandinavian, but it is a green island in a cold sea, and a lot of Irish women, slaves or otherwise spoils of war, were the ancestors of a lot of contemporary Icelanders, so not that distant, really. The romanticism and the romanticized renaissance of ancient land-based ways of poetry and spirituality is, however, very much the point, indeed.

Pound’s new father-in-law did not approve of his new son-in-law’s poetic dandering around. Lawyering was more to his taste, but, still, he loved his daughter, and so did Ezra, so they were stuck with each other, circling around each other like cocks in a betting pit.

Dorothy Shakespear Pound

The last of the those Nordic fantasists, the pre-Raphaelites, before the World Went All to Hell.

Pound and Dorothy used to sit before the fire, where Pound declaimed his poems and his enthusiasms and a lot of spiritual stuff about jewels and the love poets of Provence and such like. They went off painting watercolours together. She was quite good at it. He fussed about, trying to get his palette mathematically perfect. Eventually, he came to hate her. Irony of ironies: later, when he was declared insane (Fascist sympathies were, by the logic of the American 1940s, insane.), she was legally declared his keeper.

Raven 1: (Flying by.) For a fuller treatment of this story, I recommend Gunnar Gunnarsson’s great, semi-autobiographical novel, “The Black Cliffs”.

Raven 2: (Doing cartwheels around him.) They’re all semi-autobiographical, dear.

Raven 3: (Bravely keeping up.) Puff puff. Yeah … Puff puff. you’re right.

(They fly off to the Black Cliffs, croaking in ravenish laughter.)

Oh, right. I have to remember that this art form, the essay-fiction-blog-drama-for-page-and-screen thing based on Gunnar’s techniques needs a bit of tweaking now and then, a bit of cognitive lens-focusing, so to speak, a bit of drawing-of-the-curtains that words are naturally heir to. Let me see. (Fiddle fiddle fiddle.) Ah. Yes. There the ravens go … see them?

If you read one book by Gunnar, make it this one. Bonus: it’s in English.

Ignore the fact that the ravens look like seagulls overexposed against the sun, because, you know, maybe they are.

Raven 1: Hey! I heard that.

Shh. Here’s the plot: Two couples on a remote farm in the West Fjords (even today, it’s faster on a bicycle than a car, and a horse would be better, or a tunnel — that’s how remote the place is. It’s a good thing it’s beautiful.) run into a spot of trouble, that ends with two of them, a man and a woman, killing their spouses, who they have come to loathe, in order to be together. A lovely political allegory, with Nazi ties, which we will explore another day, that is based on a true Icelandic murder in the dark days of the past winters, before anti-depressants and solariums cheered all the Icelanders up a merry lot.

Gunnar, the Famous Writer

Still working on his cheerful look.

Pound’s solution for marrying the worlds of politics, commerce, lawyerliness and poetry was to write a poem, a lyrical entertainment, as that old way of thinking (poetry) had come to be known in the ‘modern’ world. Precisely, he hoped to write a poem that contained so many clear and innovative connections between history, mythology, literature, philosophy and economics that all thinking men and all men in government would have to read it, if they could hope to do their jobs well, or at all. Out of close to thirty years of that, he was writing stuff like this:

Imprisoned in the American Detention Centre in Pisa Italy in 1943 …

… Pound started his great Pisan Cantos on a sheet of toilet paper. When he won the inaugural Library of Congress Bollingen Prize for the completed sequence (among other things, mourning the death of his fascist heroes, and while still under a charge of treason, to boot), the common people of the United States were enraged (Mind you, that doesn’t really take much. It is a kind of quintessentially American entertainment that even Pound indulged in in his own way. Besides, they wanted romantic novels, not poetry.)

If Pound had only written this!

March 3, 1948

Definitely a missed opportunity, Ez.

The solution of post-modernist twentieth century writers, to embrace populism and effervescent, even contradictory and illogical points of view was not Pound’s way, and not Gunnar’s, either. That is actually quite understandable, given that the great populist politician of the time used to decorate his speeches like this:

Nuremberg Rally, 1934

Dangerous stuff. It was like shaking jars of nitroglycerine.

That is the plight of modernist writers even in countries or communities emerging into modernism today: they feel themselves the equals to kings, dictators, presidents, prime ministers and bridge engineers, yet all they are given to assert their practical status are tools that most people read as if they were the stuff of fairy tales and wall decoration.

The Lady of Shallot, by John William Waterhouse

In 1907, Gunnar left Iceland for Denmark. In 1908, Pound left the United States for London. Waterhouses’s painting above is the world of modernism, on a foundation of Nordic fantasy, that they stepped into. It took them into at first differing but then converging directions. It was out of beginnings like this that Pound and Gunnar tried to counter Nazisms own modernized (so to speak) versions of Nordic myth. Entire literary genres sprang up along these lines, including the great German genre of the country physician, which became a dominant art form of the German propaganda ministry during the Third Reich and lives on gloriously in German television soap opera (which played, by the way, a strong role in bringing down the Iron Curtain.) These things live on, I tell you!

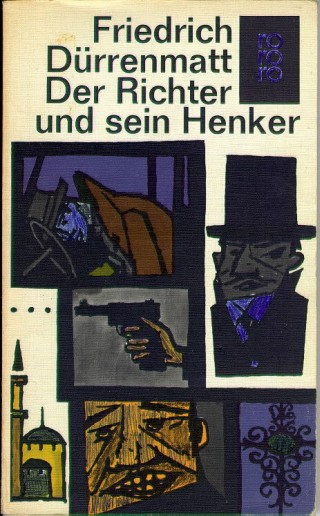

What a mess the world can be for a modernist writer hoping for a bit more push and a bit less pull, though. The Swiss playwright, Friederich Dürrenmatt, who had toyed with Nazism when he was young and was wracked by guilt about it for the rest of his life, chose to deal with it by creating plays that were not dramas at all but trials, very bitterly funny trials, of his audience. He hoped to show every audience member his or her own guilt (Yes, Original Sin can be read into that. Dürrenmatt was the son of a pastor, after all — a Swiss pastor, and that means a lot.), and to leave them talking over the ethical dilemna of his plays in the coffee houses of Bern and Zürich, where they could eventually resolve them — not on the stage but in Swiss society itself. Pretty brilliant, really. He was of the generation following Gunnar’s, yet very much of Gunnar’s time and dealing with the issues from a culture and society remarkably similar in many ways to that of Iceland earlier in the century. Everyone was becoming modern, but no one knew the rules. The rulebook of God was more or less gone. It was left to the last holders of its traditions, novelists, of all things, to make a stab at rewriting it. Here’s one of Dürrenmatt’s attempts:

The Judge and His Hangman

One of Dürrenmatt’s comedic crime novel sermon adventure trial objects in a Cold War West German edition.

I hope you don’t mind my showing how Gunnar’s interests were actually central to his time and took place within a particular context, because it was that context he was responding to.

Raven 1: Get on with it. We’d rather you herded some sheep.

Raven 2: Yeah, isn’t it lambing time yet? There’s lots to eat at lambing time.

Hang on, guys, if it’s dead things you want, I think I have just the thing for you. It’s a little bit of a detour down a darker road, but …

Raven’s 1 & 2: Darkness? Oh, goody!

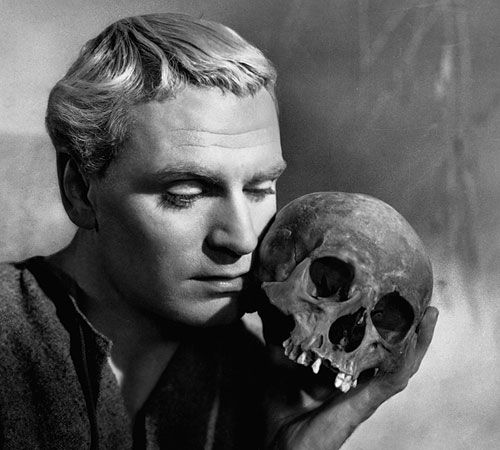

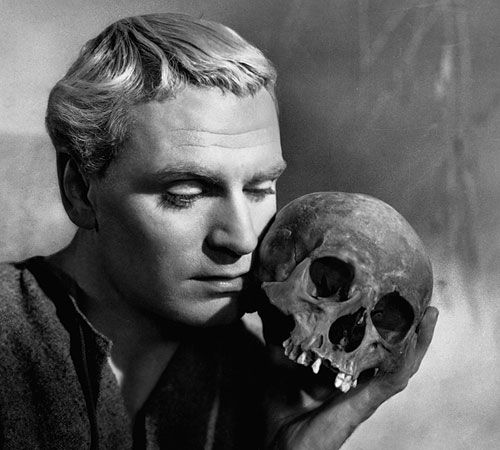

Laurence Olivier, Hamlet, 1948

The actor contemplates the war just past.

I thought you’d like that.

Ravens 1 and 2: Oh we do, we do!

Raven 1: Yes, we’re glad you’ve recognized that the plight of writers trapped within words and popular impressions of what words can do is not a problem unique to the 20th Century. Modernism started long before that, in England. We should know.

Raven 2: That’s true. Shakespeare recorded the moment in his play Hamlet, he did.

Raven 1: Well said, my love!

Raven 2: Why, thank you. There he wrote the clever and blatantly literal line, “Words, words, words,” and then, to get out of his own head, made his character, Hamlet, say them out loud …

Raven 1: … the poor duff …

Raven 2: So true! A melancholy Nordic philosopher prince who had returned to conservative, pre-modern, pre-humanist and Nordic Denmark from a modernist, Lutheran, self-confessional university in Germany on the cusp of humanism and modernism.

Raven 1: Poor Hamlet.

Raven 2: Heck, poor Gunnar.

Raven 1: So true. Still, like Hamlet, he tried to make the best of it. Here’s what Gunnar had to say about that.

(Dear Reader, ravens, like actors, like writers, try to have some fun with all this grim-ness …)

Kenneth Branagh Really Trying to Get Into His Role as a Melancholy Dane

Shakespeare had more earnest designs for his character: he wanted him to read fate and receive clear answers, in the way a priest once read the Soul or the Book that was God’s World. I mean, they were even in Capital Letters, so you could find them easily in a hedgerow of words and thoughts. In the modern world, of course, the self-confessional, Lutheran one, there are no clear answers. What was Hamlet left with? Harumph, Hamlet was busy trying to read his soul …

Soul: Definition from the Dictionary of Earth and Air, 1908 Edition

A new-fangled private thing, which had recently before been public, partly because in the world of the Medieval Church souls were public and partly because he was a Prince, and thus the state, yet whose rightful place in the social role accorded this public identity had been usurped by a murderous uncle.

Sigh, isn’t that the way. Anyway, while Hamlet was trying to read the pattern of his thoughts, like some kind of Nordic Buddha, the old courtier Polonius asked him what he was reading …

Polonius: What are you reading, my Lord?

And Hamlet? God’s minister of state on this vale of tears? Was he able to say, “Your soul, sinner?” No. He was stuck with the words of some author. There he was, a trained philosopher, in such an embarrassing position. But he was a trained philosopher, so he answered precisely, although not without frustration: “Words, words, words.” He held up his book to make his point. What were once words recording God’s creative speech that put the world into perfect order, were now just nearly inscrutable words on paper, that a man could make mean pretty well anything he wanted them to, that some “writer” was forcing him to speak, and which he had to figure out how to speak with some shard of dignity. What a task! He waved the book around for emphasis of his predicament, like this:

Polonius and Hamlet Can Hardly Believe the Embarrassment of It

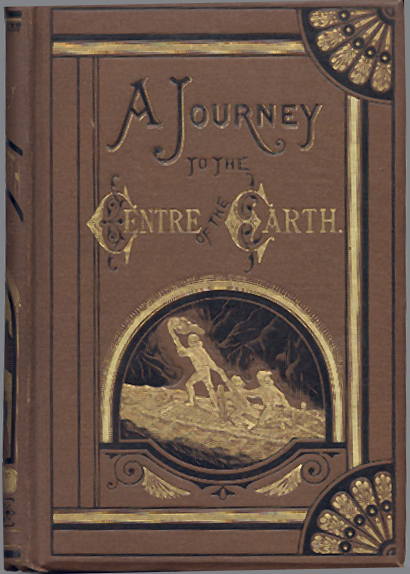

It was as if Hamlet had been caught reading some kind of fantastical, titillating entertainment or something not befitting of an earnest, enlightened philosopher, like, oh…

… or this, of all things …

Actually, that was pretty much the case. Still, frustrating, right? Gunnar might have entered this story 4 centuries late (that’s how far Iceland was from England at that time), but that doesn’t mean that he didn’t rightfully feel some of the same bewilderment as Hamlet did at his own moment of crisis. As he told the students at Herthadalen on June 15, 1926 (He uses a shipping metaphor, because he has been trying to suggest that the countries of Scandinavia are naturally united and protected by the sea) …

Outside our port stands Fate. We do not see her, but she stands there. And even for those who see her, her face is veiled: no one can read in it!

(From “The Northern Kingdom”, 1927)

It’s a downer, for sure. It’s like looking off of the Icelandic shore towards Europe, or off of the Danish shore, anywhere, in the winter, and seeing only:

Another Cold Writer Staring Back

This is called the height of the Icelandic summer, Arctic Circle version.

And to think that all you wanted was a bit of light. Now, to be serious. I loved my day there at the northern tip of the Icelandic mainland, and my Canada is a nordic nation as well, which I will get into on another day, and as a man of northern earth, just as Gunnar was a man of northern earth, I know well enough that the fog is its own language and is full of light. Gunnar would come to that eventually, but it would take time. After all, he had been trained in literature, as was Hamlet, in a different tradition. In his novels, as in his politics, he tried to put them together into one. During these attempts he consistently avoided Shakespeare’s solution, tragedy, or Hitler’s, smarmy romance and shell-shock, or Pound’s, rage and bitterness and impotence, and tried to find a middle way. I admire that deeply. Tomorrow, I will honour it. For now, thank you for playing along.

Today Dürrenmatt’s old villa above Lac Neuchatel has been turned (on his bequest and with his financing) into a museum of … not his great twentieth century plays or his semi-autobiographical detective novels but his paintings, drawings, etchings and, well, look …

Today Dürrenmatt’s old villa above Lac Neuchatel has been turned (on his bequest and with his financing) into a museum of … not his great twentieth century plays or his semi-autobiographical detective novels but his paintings, drawings, etchings and, well, look …

Icelandic Pool with Line, Skutustaðir

Icelandic Pool with Line, Skutustaðir