Don’t look behind you.

You’re not here to enter nature. Or are you?

Or are you?

It’s your call.

In the global city, money is made and stuff is imported from the world. This stuff is often cheap, as a representation of Icelandic global economic clout, although it does represent wealth and connection.

Often the process of Icelandization is to treat this adopted material with humour born of poverty. Jokes of this kind are serious business. They warm a cold world.

Just a few metres away from a ruined farmhouse.

…some people cross the line to make images of themselves…

… or of nature…

… but not of how to live in it…

… not of how to be home, or of how that continues when you leave.

Or of what it means to stay.

The earth is a social space.

Human society is something different.

Nature becomes a space of disobedience. This is called freedom.

Isn’t it time to go home to the earth?

When you live there, there is no nature.

When you live there, there is no nature. There is a different freedom.

There is a different freedom.

Obedience.

Not everyone can leave for the city.

Some farms in Iceland are in the most marginal patches of grass in the midst of lava fields. Here’s Thor’s Shield, the mother of all shield volcanoes, at the peak of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where it crashes into land underfoot. There’s a little bit of grass here in Thingveillir, but not much.

Lots of wind, though, which makes it a great place to take some of that grass and build a house.

Sandgerði

Beautiful, isn’t it. Every farm in the country has ruins of turf houses like this. That’s the thing about Icelandic views: it’s the fact that people live on this land that makes it beautiful. The hard work of warming the land has been done. After all, the story here is one of settlement, not of conquest.

The sea and the land have teeth.

The Ölfusá Meets the Atlantic at Óseyartangi

The Ölfusá Meets the Atlantic at Óseyartangi

For human beasts, life and death are a series of crossings. For earth, water and wind, three living forces humans wade through, it is a great mixing together.

The Ölfusá Meets Tides and Waves in the Wind

The Ölfusá Meets Tides and Waves in the Wind

In a country in which the social lives of humans, and all they have built together, appear less substantial than the forces they live among …

Barely. With a lot of improvisation.

It is enough. In this land, lighthouses are not just about visible light.

In a country in which a beach is the sound of the keel of a ship being hauled by men on pebbles up out of the surf (strand) or of men walking through the dunes (sand), houses and lights are all shores.

What you wash up as is not always your choice. Every landing is also a strand-ing. You might live or you might die. For centuries, Icelandic men went to sea in wooden boats, and came in through the surf to land, not always well.

What you wash up as is not always your choice. Every landing is also a strand-ing. You might live or you might die. For centuries, Icelandic men went to sea in wooden boats, and came in through the surf to land, not always well.

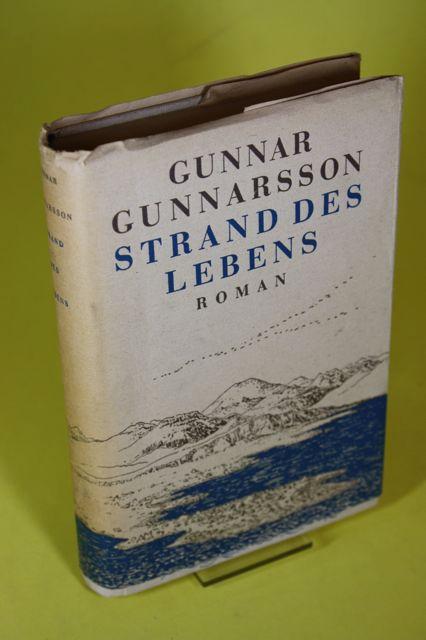

Your fate is not whether you make it alive or dead, but how you face it. That’s grim, but then some things are. Gunnar Gunnarsson wrote about this fateful beach surrounding Iceland during the devastation of World War I. The book was Livets Strand. In German, it was translated as Strand des Lebens.

Your fate is not whether you make it alive or dead, but how you face it. That’s grim, but then some things are. Gunnar Gunnarsson wrote about this fateful beach surrounding Iceland during the devastation of World War I. The book was Livets Strand. In German, it was translated as Strand des Lebens.

In English, the title would be The Shore of Life, but it has never been translated into English. It is an allegory of that war, set in a remote Icelandic fjord. It is the unique, life-affirming, and devastating story of a pastor wrestling with his faith in terrible circumstances, tried by the beauty and horror of life and the often-times inability to distinguish it from death. It is a writer wrestling with how to tell the difference. In an Icelandic context, it is a shore. In this time in which we need it, in many languages. We are at sea.

In English, the title would be The Shore of Life, but it has never been translated into English. It is an allegory of that war, set in a remote Icelandic fjord. It is the unique, life-affirming, and devastating story of a pastor wrestling with his faith in terrible circumstances, tried by the beauty and horror of life and the often-times inability to distinguish it from death. It is a writer wrestling with how to tell the difference. In an Icelandic context, it is a shore. In this time in which we need it, in many languages. We are at sea.

In Breiðafjörður, the wide fjord of West Iceland, people know a lot about water.

They live with it.

One can presume water knows a lot about people, too.

In Stykkishólmur, halfway to the far west, where land ends, people know about harbour, where land and water and people mix and voyages begin.

On the hill above the harbour there is an old library.

From it, you can read people reading the water and read the water writing the world.

You can also play chess.

This is the Library of Water.

Water from Iceland’s glaciers is here to be read.

To reveal itself.

Shelved with the shelves of the world.

Among houses for water.

And houses for people.

Water reveals itself here.

People come to be written by it.

And to see their world with new eyes.

They come to see with the eyes of water.

And to play a little chess.

Your move.

Think again. This is a nature preserve in the Whale Fjord in West iceland. It is also one of the runways of the fighter base that protected the Allied Fleet during the Battle of the Atlantic during the early 1940s. Here’s another view. Back then, this fjord would have been filled with ships, protected by fighter cover and a submarine net across the mouth of the fjord.

It is also one of the runways of the fighter base that protected the Allied Fleet during the Battle of the Atlantic during the early 1940s. Here’s another view. Back then, this fjord would have been filled with ships, protected by fighter cover and a submarine net across the mouth of the fjord. This is the naval base today.

This is the naval base today.

Iceland has, wisely, left this history almost unacknowledged, and has given this land to the birds. We can honour that forever. We don’t have to stop honouring that wisdom any time soon.